Among the innovations of the new One Big Beautiful Bill Act is handing huge sums to the Pentagon without asking for justification in advance or offering clear direction for their expenditure. Some may tout this flexible approach as a boon to national security, but it is far more likely to produce the opposite: wasteful, deficit-fueled spending on abortive programs that ultimately hurt the military more than they help it. With House Speaker Mike Johnson already floating proposals for more reconciliation bills, it’s important to understand why.

Typically, the Pentagon’s spending is laid out in the annual Defense Appropriations Act, which allocates funds at the account level across the military’s various agencies. The funding tables that accompany the bill specify amounts for individual programs and sometimes even projects. The instructions in these tables aren’t technically binding, but the Pentagon traditionally follows them.

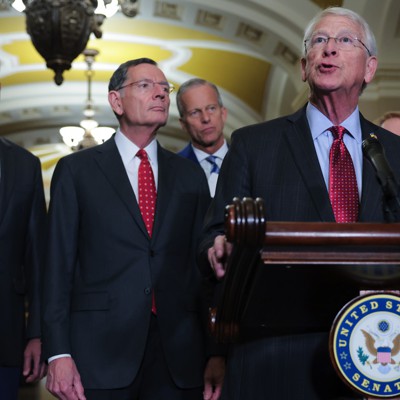

Last week, Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., and Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Ala., chairmen of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, sent letters to the Pentagon and the Energy Department laying out how they’d like these agencies to spend the $156 billion for national security included in the recently enacted OBBBA. But the letters—and their funding tables for the Pentagon, military construction, and the National Nuclear Security Administration—look more like rough notes on congressional intent than a clear set of instructions.

For starters, the line items in the tables generally do not specify which fiscal year the funds are intended for. In a few cases, they include notes like “funding intended to pay outstanding bills in FY25 or forward-fund FY26 partial bills…” or “FY25/FY27,” but for the most part, the tables don’t specify the fiscal year at all. Many of the line items cover multiple accounts, effectively leaving it up to the Pentagon to distribute funds between service branches and their accounts as it sees fit, and many of the line items do not break down funding beyond the overviews included in the reconciliation bill text.

Further underscoring the lack of detail behind these instructions, nearly every line item includes a request for either a meeting or a spending plan from the appropriate Pentagon office or offices.

But it’s not clear that the Pentagon has such plans.

When the Defense Department submits its annual budget request, it generally includes thousands of pages of justification documents, clearly describing how it intends to spend the money. But this year’s books fall short of a clear plan to spend the $113 billion that the president requested through reconciliation. For instance, the first of the Army’s justification books for Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation lists a $100 million request for reconciliation funding for Tank and Medium Caliber Ammunition, alongside an $85 million request for the program through traditional defense appropriations. But the justification book that includes the program element for this line item (PE 0603639A) only includes the $85 million, not the additional $100 million in reconciliation funding, let alone a description of how that $100 million would be divvied up between projects and to what end.

In another example, the Navy’s Shipbuilding and Conversion justification book does not include a base-budget request for the Ship to Shore Connector program, an account that the Pentagon has zeroed out in its funding request for the last two years, and that Congress has continued to fund anyway. However, the justification book includes a request for $239 million for the program through reconciliation. This suggests that the Pentagon did not feel this funding was necessary, at least until Congress outlined its plans for boosting Pentagon spending through reconciliation. Still, perhaps owing to sheer force of habit, Congress upped the ante on the Pentagon’s request, appropriating $300 million for the program in the reconciliation bill.

But the new gold standard of funding things without a plan is the money allocated to the Golden Dome air-defense project: some $24.4 billion for a program that physicists have described as a “fantasy.” Even Space Force Gen. Michael Guetlein, the newly appointed Direct Reporting Program Manager for Golden Dome, admits that the program may not be feasible. As he explained last week, “What we have not proven is, first, can I do it economically, and then second, can I do it at scale? Can I build enough satellites to get after the threat? Can I expand the industrial base fast enough to build those satellites? Do I have enough raw materials, et cetera?”

These are major questions, and if any one of them comes back with a “no,” Congress will have just poured nearly $25 billion into a program that may literally never get off the ground. That’s roughly the cost of two Columbia-class submarines.

Pentagon spending is supposed to reflect a comprehensive strategy for national defense—but when it comes to the Pentagon dollars included in reconciliation, the lack of detail in both the budget justification documents and the congressional funding tables show that Congress just greenlit a $156 billion spending spree with no clear plan for how that money will be spent. That’s why most line items in the tables request a spending plan from the Pentagon.

The problems with this approach don’t end with the high risk of wasting billions on programs that may never deliver, or that we simply don’t need. The sheer scale of the spending boost for national security—a nearly 12 percent increase, assuming 2026 spending mirrors the president’s budget request—is also deepening the nation’s debt, imperiling our ability to meet our national defense needs in the future. Interest payments on the nation’s debt hit the trillion-dollar mark last year, and are projected to do so again in 2026. Amid this deepening crisis, budgeting for national security in the medium- and long-term requires fiscal restraint and strategic prioritization, not a “shoot first, ask questions later” approach to spending on an unprecedented scale.

Furthermore, because budget reconciliation can pass with a simple majority, it has become an utterly partisan endeavor. National-security spending is one of the few places where lawmakers traditionally reach across the aisle and work together to advance a common vision for national defense. Budgeting for national security through reconciliation rejects that bipartisanship and threatens to turn national-security spending into a seesaw, with funding for programs Republicans favor in some years, and funding for programs Democrats favor in others. If this precedent becomes standard practice, we can expect the waste of vast amounts of taxpayer dollars and of military time and energy.

This might all seem like a moot point, given that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act is now the law of the land. But with House Speaker Mike Johnson floating plans for another round or two of budget reconciliation in this Congress, this new model for Pentagon spending could become standard operating procedure. The risks of budgeting for national security like this year after year extend far beyond the billions of dollars of waste this one-off spending binge may generate. It threatens a new era of partisan Pentagon spending underwritten by the fallacy that more spending always makes us safer. The truth is it doesn’t—smarter spending does.

Gabe Murphy is a policy analyst at Taxpayers for Common Sense, a nonpartisan budget watchdog that advocates for transparency and calls out wasteful spending.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply