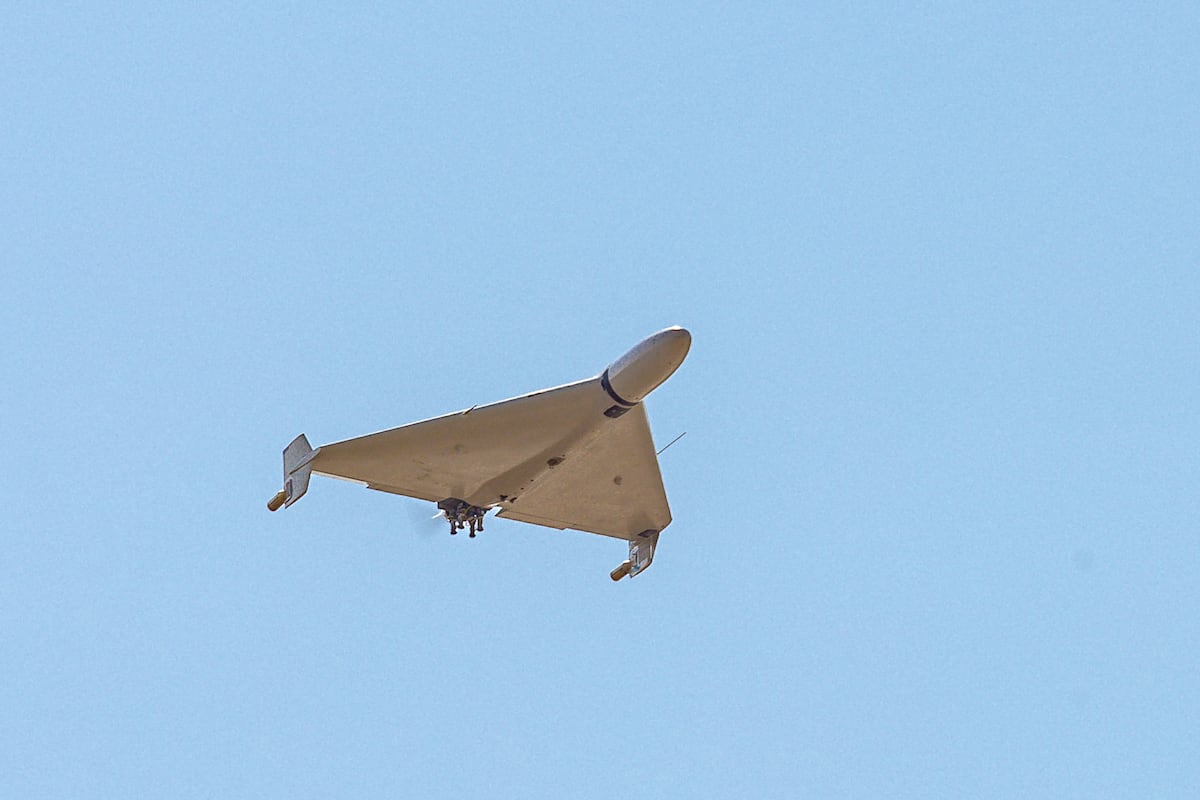

Whatever the next chapter of U.S. air power will look like, there will be drones — and lots of them — accompanying manned fighters into battle.

But as Air Force leaders translated their vision into an acquisition strategy, a novel meeting of the minds — at least by Defense Department standards — may have saved the service from a major miscalculation: A new cohort of so-called collaborative combat aircraft, as originally envisioned, wouldn’t be able to fly far enough to be effective in combat, which would have been a serious problem in the Pacific theater.

That’s according to acquisition chief Andrew Hunter, who spoke about the episode anecdotally to stress how the Air Force had changed its acquisition practices by soliciting early input from stakeholders who were previously consulted only later in the process.

Key to catching the range shortcoming, he said in a July interview, was the unique approach the Air Force took to buying the autonomous drone wingmen known as CCAs. The service brought operators from Air Combat Command into the room alongside acquisition experts, who would normally have taken the lead on a major procurement like this.

“We had … a lot of discussion about range to understand operationally, what was meaningful and what was going to be effective,” said Hunter, the service’s assistant secretary for acquisition, technology and logistics.

With ACC operators’ insights, he said, the Air Force was able to push contractors to find the “sweet spot” of enough range, at a reasonable price and on the right timeline.

That approach to acquisition is a hallmark of the Air Force’s operational imperative effort, Hunter said, and could change how the service procures systems in the future.

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall rolled out his wide-ranging, seven-pronged operational imperative plan in March 2022, seeking to transform everything from how the Air Force deploys and sets up bases in war zones to procuring advanced aircraft — including CCAs, the Next Generation Air Dominance future fighter and the B-21 Raider stealth bomber — and finding better ways to track and target enemy forces.

With the Biden administration’s term nearing the finish line, Kendall’s operational imperative transformations could prove to be his lasting legacy on the Air Force.

And such modifications are already guiding other changes to the force. In a Sept. 4 panel at the Defense News conference, Hunter said the operational imperatives were the “genesis” of a broader restructuring of the Air Force, called the reoptimization for great power competition, that was unveiled earlier this year.

Along the way, the operational imperative effort also prompted the Air Force to rethink how it does business and procures new aircraft and other systems, in particular by bringing the operational and acquisition communities together.

From the start, Hunter said, each team working on an operational imperative effort was co-led by an acquisition expert and an operational expert, so each perspective was equally balanced. The systems eventually developed will be used by the Air Force’s operators, so involving them each step of the way was logical, he added.

The rapidly moving acquisition process involves so many decisions — everything from choices on designs, contracts, schedules and how systems will be used — that there’s no time to waste on creating systems that aren’t immensely useful.

“It’s not one of those cases where we get a requirement, and then we in the acquisition community run off and do our thing, and then we come back at the end and say [to operators], ‘Here it is, hope you like it,’” Hunter said. “If they don’t scratch the operational itch, then we’ve not succeeded.”

The time has come, Hunter added, to move away from the lengthy, traditional model in recent decades of sending requests for proposal to a limited number of major firms and only picking one. Instead, the Air Force wants to move to a “next-generation” acquisition model that continually works with a range of industry partners and iterates multiple designs over time.

The Air Force’s CCA program is the most prominent example of this approach. The service in April announced it had selected Anduril and General Atomics for the first “increment” of the drones. And a second increment is on its way in fiscal 2025 — one that could produce autonomous drones dramatically different from the first batch.

“Do not assume, and it may not be, just an evolution of increment one,” Hunter said Sept. 4. “It could be an entirely different set of missions; it could be an entirely different kind of an aircraft.”

Chasing threats

As the service works on operational improvements, threats faced by the United States continue to evolve. China, in particular, is focused on strengthening its own military for a possible invasion of Taiwan — and is doing so “incredibly quickly,” Hunter said.

“The threat’s not sitting still,” Kendall said in a June interview with Defense News at the Pentagon. “It’s getting worse, and it’s … very creative.”

So, the Air Force adjusted its plans, supplementing its modernizing effort with other “operational enablers” that cut across multiple areas. The service also needed to improve capabilities, especially through greater munitions, better electronic warfare and mobility — like an envisioned future stealthy tanker, dubbed NGAS, for its next-generation aerial refueling system.

And the Air Force changed course on Next-Generation Air Dominance, a future fighter family of systems expected to replace the F-22. The price tag for each NGAD, as originally conceived, would likely have been about three times the cost of an F-35, Kendall said. The NGAD program is now on hold while the Air Force reconsiders its design, and it is unclear when the service will award a contract.

The imperatives were built around a “focus on operational problems we need to solve,” Kendall said. “What are the things we need to figure out to make sure we’re competitive and stay ahead of other threats?”

Kendall said the Air Force is making progress on these imperatives, though he tempered his comments by noting that funding limitations and shortfalls in cybersecurity and other technology have kept the effort from moving as quickly as he hoped.

“I’m always impatient,” Kendall said. “I want to go faster to get militarily meaningful quantities out into the force that make a difference operationally.”

When Kendall announced his operational imperative plan, work was already well under way on the 2023 budget proposal. This meant the first time the Air Force could request funding for new operational imperative efforts was in the 2024 budget cycle.

But Congress threw the Pentagon a curveball. Disputes on Capitol Hill held up the military’s 2024 spending bill for months, and the fiscal year was already half over when lawmakers finally passed it.

While the 2024 budget delay hindered much of the operational imperative effort, Hunter said, some elements — such as the command, control, communications and battle management, or C3BM, effort — were already under way or had existing funding to get going.

The Air Force was able to move quickly to field C3BM capabilities, such as the cloud-based command and control effort that knit together several different air defense data sources to better defend the homeland. Hunter said that was able to be fielded rapidly over the last two-plus years or so, and has been successful.

And because the program to develop CCAs was already under way as part of NGAD and had “significant” funding, the Air Force was also able to keep it rolling despite the 2024 budget delay, Hunter said.

But as budgets get tighter, it remains to be seen whether the OI project will receive the funding it needs.

A lasting impact?

The Air Force’s desired funding for operational imperative efforts grew from about $5 billion in 2024 — once the budget was passed — to $6 billion in the 2025 budget request.

Kendall said he’s hoping to maintain full funding in 2026, but expects tight budgets to force the service to make “difficult choices,” including whether the OIs will get the funding he wants.

The growth of additive manufacturing, and technology advancements making it possible to conduct distributed manufacturing for high-end military capabilities, are also helping the Air Force create its new procurement model, Hunter said.

“You can scale more rapidly,” he said. “You can maybe work more intimately with partners and allies … which is definitely important to our strategy of integrated deterrence. You can do complex designs more affordably. These approaches are very consistent with rapidly adopting those technologies into our production and design processes.”

Hunter feels strongly that this approach to procurement — with tighter cooperation between acquisition experts, industry and operators and more frequent iterations to evolve designs — will one day become standard for the Air Force, and perhaps other services.

“This is the way to do it, now and in the immediate future,” Hunter said. “I don’t see a date where it will become less relevant.”

And it’s not an entirely new approach, he said, but it is a habit the Air Force had gotten out. He compared this strategy to that of the World War II and post-war eras — when aviation technology transformed by leaps and bounds — as opposed to the late-Cold War era of the 1980s and 1990s, during which the pace of advancements slowed.

“Change was happening so fast” during WWII, Hunter said. “And you see … how quickly we were able to develop rockets and missiles in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The pace of change and progress was so fast that it drove us towards these more tight-knit relationships among experts.

“It’s not unprecedented, but I definitely think it’s a little bit of a ‘back to the future’ scenario of behaving a little more like we did in those earlier periods.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply