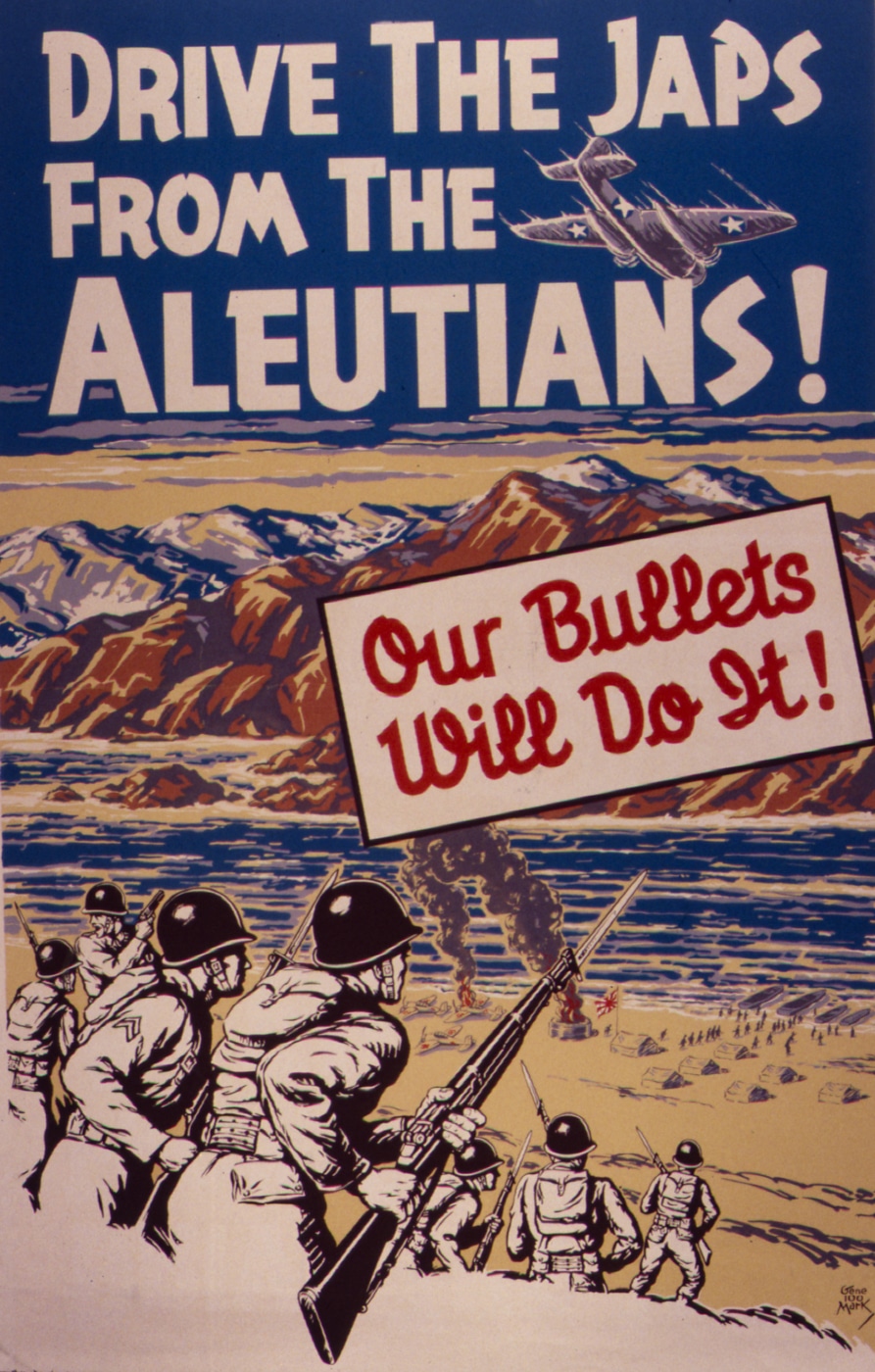

The Aleutians Campaign must be the most misunderstood and under-appreciated strategic contest of World War II. You can find all the movies, novels, historical studies and analyses imaginable on war in Europe, the South Pacific, North Africa and the Mediterranean, but Google the Aleutians circa 1942-43, and results will be relatively sparse, focusing primarily on combat actions on the flyspeck islands of Attu and Kiska.

However, there’s so much more to this brutal air, land and sea struggle against Imperial Japanese Forces. In fact, it was the only ground campaign of the war primarily fought on North American soil.

More importantly, the Aleutians Campaign was a long-distance, wide-ranging fight for strategic positioning in the American Theater of Operations. Japanese forces in the early years of the war felt it crucial to occupy positions in the Aleutians to protect the northern flank of an expanding empire.

Despite early conjecture to the contrary, the Japanese never considered their Aleutians operations as an offensive designed to give them a staging point for a potential invasion of the United States. What concerned Imperial Headquarters in the spring of 1942 was potential for an Allied attack on their home islands staged through the Aleutians.

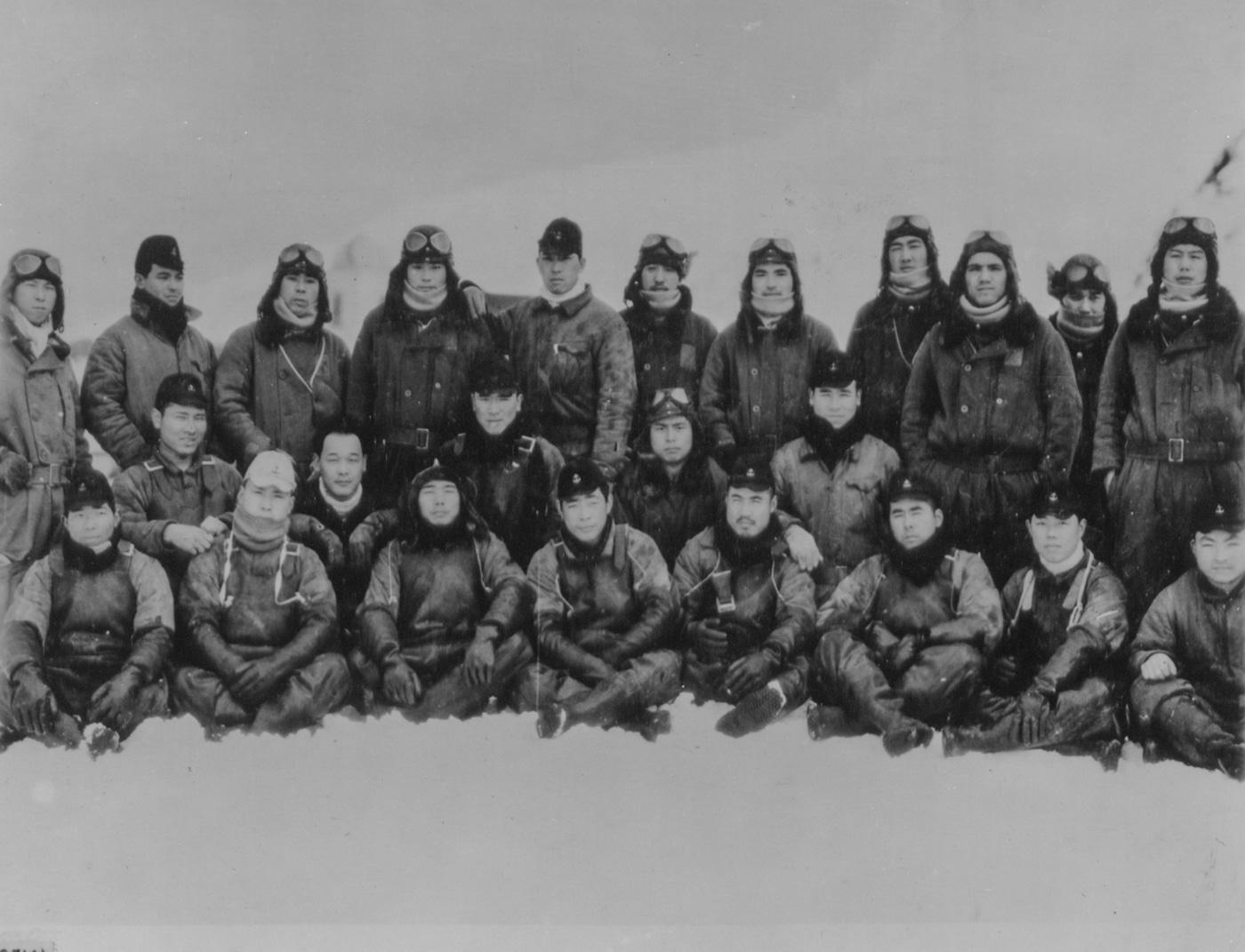

Such fears led Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, primary architect of Japan’s planned conquests in the Pacific, to form an occupation force aimed primarily at bases on Kiska and Attu and supported by their 5th Fleet of two light aircraft carriers, two heavy cruisers and three destroyers.

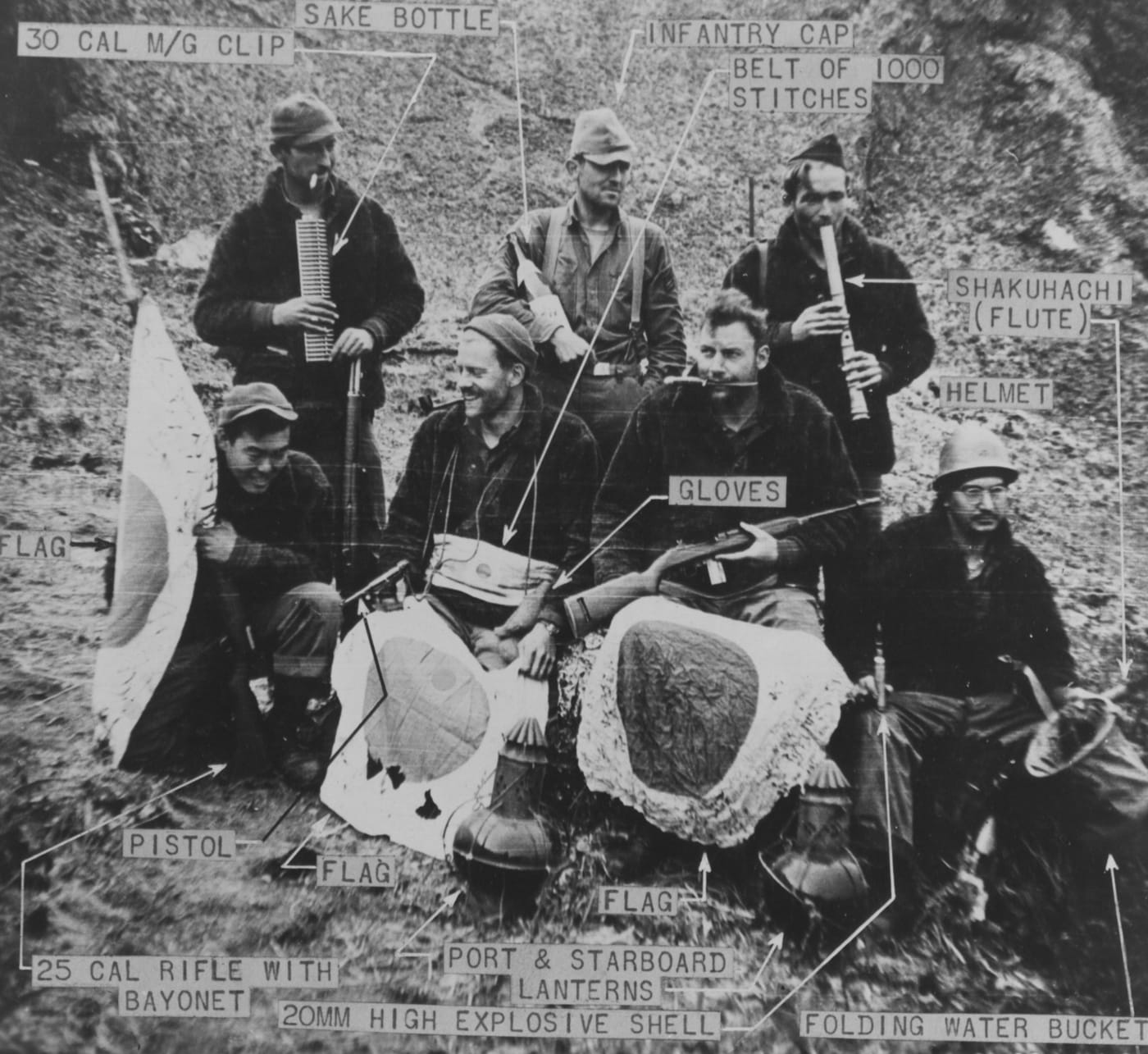

Ongoing attrition from battles elsewhere in the Pacific kept the available air support at a ragged minimum but in early June, Japanese aircraft from the two carriers struck the Naval Air Station at Dutch Harbor on the eastern Aleutian island of Unalaska. Not much damage was done and the Allied command even scored an unexpected intelligence coup after the Dutch Harbor raid.

A single Japanese Zero, struck by an errant machinegun round, crash-landed on nearby Akutan Island. The pilot was killed, but the aircraft survived relatively intact, giving the Allies a first in-depth opportunity to study the formidable Japanese fighter. [You can read more about this incident in Tom Laemlein’s article on the Tactical Air Intelligence Unit.]

Flash Forward: A Controversy Arises

The Dutch Harbor air strikes coupled with reports of Japanese troops heading for landings on the islands of Kiska and Attu were questionable moves from a post-war perspective. They created an ongoing controversy among military scholars.

The timing led some to speculate that it was all merely a feint designed to draw attention away from what Yamamoto had in mind to destroy the U.S. Pacific Fleet farther west. Some historians and analysts insisted for decades that Yamamoto was using the Aleutians campaign to lure U.S. carriers away from his planned attacks on and around Midway.

That’s unlikely due to the twin tyrannies of time and space. Dutch Harbor is nearly 3,000 miles from Pearl Harbor, and yet Yamamoto scheduled both his Dutch Harbor attacks and the Midway fleet action for the same day, 3 June 1942. A 24-hour sailing delay pushed the Midway fight to 4 June.

Regardless, there was insufficient time for Dutch Harbor to serve as a diversion. And Yamamoto’s submarine screen, designed to keep him apprised regarding U.S. carrier movements, was spread out between Pearl Harbor and Midway rather than between Hawaii and Alaska. Yamamoto was focused on a decisive fight at Midway and relatively unconcerned with any Allied reaction to his moves in the Aleutians.

A clincher to the Aleutians as tactical feint argument is likely the total lack of any claim in Japanese records of the time that activities in the western Aleutians was any sort of planned diversion.

Japan’s Opening Gambit

In the real world of summer 1942, Japan remained compelled to safeguard against any Allied moves on their northern flank. They began to occupy some positions along the formidable Aleutians chain with the twin missions of holding ground and building operational airfields to support further potential operations in the strategic area off the Alaskan coast.

Despite truly nasty weather, including persistent fog banks, low visibility and ceilings, rain, and arctic temperatures, a Japanese North Seas Detachment put some 3,000 troops ashore, including the 3rd Special Naval Landing Force on Kiska and the 301st Infantry Battalion on Attu.

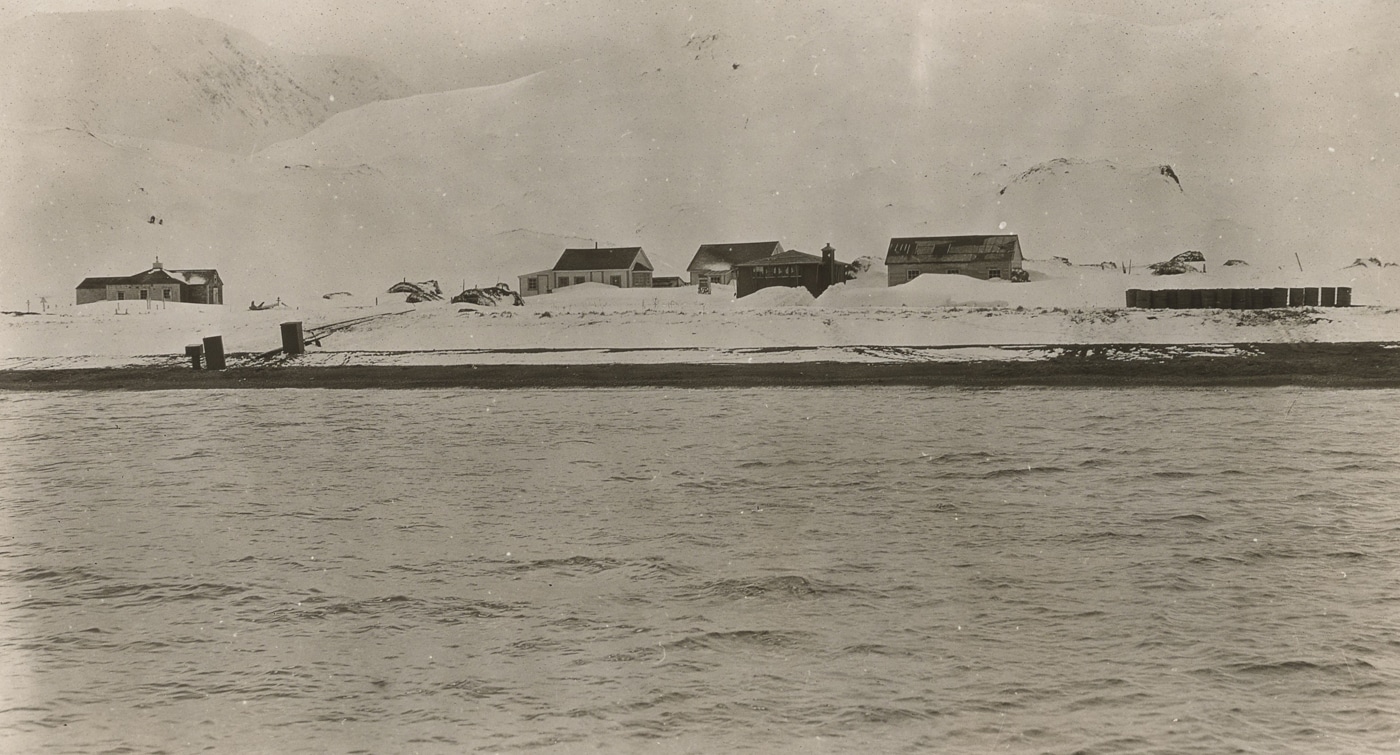

The Japanese landing on Kiska came as a surprise to the 10-man Navy weather team stationed on the island as well as some 40 native residents. Within days, all but one of the sailors became POWs along with the entire native population, including an American couple who attempted suicide to avoid capture.

The elusive sailor, Aerographer’s Mate William House, avoided detection for 50 days before he was finally captured. All but one of the Kiska residents at the time of the Japanese landings in June 1942 survived the war as prisoners in Japan.

Imperial Forces Dig In

The landing forces on both islands included a mixed bag of light and medium artillery pieces plus anti-aircraft weapons. Designed as garrison/defensive outfits, the Japanese Army contingents included labor formations tasked with building vital airfields.

While the manpower was adequate, the conditions on both islands as the Alaskan winter approached precluded any real progress. Japanese garrisons lacked engineering skills and the proper heavy equipment needed to convert the rugged islands into bases for offensive power projection.

Unable to accomplish that crucial mission, Japanese labor on Attu and Kiska focused on building impressive defenses. Both the lack of operational airfields and those impregnable bunkers would play significant roles in the ensuing Aleutians Campaign but the Japanese weren’t overly concerned at the time. What the commanders on Attu and Kiska worried about was logistics.

Japanese Logistics — Supplying the Aleutian Occupiers

Demands from other war fronts sucked Japanese shipping resources away from the Aleutians, and they were faced with no regular or reliable way to deliver equipment, supplies or reinforcements to their garrison forces on the rugged archipelago that sweeps some 1,200 miles westward from the Alaskan mainland. Much of that area was either patrolled by Allied warships or covered by bomber and fighter aircraft.

Japanese occupation forces were stuck out on a precarious limb, but they had to content themselves with just holding on to what they’d gained, feeling confident that the weather and terrain would be too much for the Americans to handle when they inevitably reacted with ground forces.

In the last half of the first full year of World War II, it was clear to the Japanese high command that their war would be won — or lost — on battlefields far from the Aleutians. That turned activities there into a less important secondary front that could not be allowed to siphon off vital combat power.

As a consequence, the Japanese planned to remain on Kiska and Attu only until the winter of 1942, at which point gains in other campaigns around the world would make it safe for the Japanese footholds in the Aleutians to be abandoned. Call it hubris, but to the Japanese high command, flushed with conquest elsewhere in the Pacific, it seemed like the safe play.

An American Perspective

A few outraged politicians and some armchair generals in the American camp at the start of World War II viewed Japanese activities in the Aleutians and elsewhere off the Alaskan coast as a prelude to an invasion of the U.S. mainland.

Military professionals saw it differently. They believed, many from first-hand experience or Canadian expertise, that the undeveloped territory was too hostile to serve as any kind of springboard for ground operations. Pure geographic sprawl, plus arctic climate and mountainous terrain, made for a brutally punishing battlefield that would preclude an enemy invasion from Alaskan territory.

All that considered, Alaska was still American soil populated by U.S. citizens, which made Japanese presence in the territory an unacceptable affront. Pressure mounted to do something about it before America and her Canadian allies lost any further face.

American Command

The Alaskan theater at the outset of World War II was unofficially a joint U.S. and Canadian command. It was complex and hampered by international concerns over strategy and tactics. As commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet as well as geographical Pacific Ocean Areas, ultimate responsibility for operations in the northwestern Pacific fell to Admiral Chester Nimitz.

Alaskan operations fell under the American Western Defense Command, with headquarters at San Francisco’s Presidio and commanded by a U.S. Army three-star general. The subsidiary Alaska Defense command, run by firebrand Army Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., was at Ft. Richardson, Alaska, with subordinate Navy and Army Air Corps commanders either advising or subordinate to him.

Most credit Buckner (later KIA on Okinawa while commanding the US 10th Army) for pushing a 1941 mutual defense agreement between the U.S. and Canada to bring Canadian Forces into the Aleutians Campaign.

Reinforcements came in the form of ground, naval and air forces from the Royal Canadian Navy, Canada’s Western Army Command, and the RCAF Western Air Command. Committing sparse Canadian forces to the Aleutians counter-moves was a tough sell for Ottawa. As a part of the United Kingdom, Canada was subject to British demands for manpower and equipment elsewhere in the world with a growing focus on war in Europe.

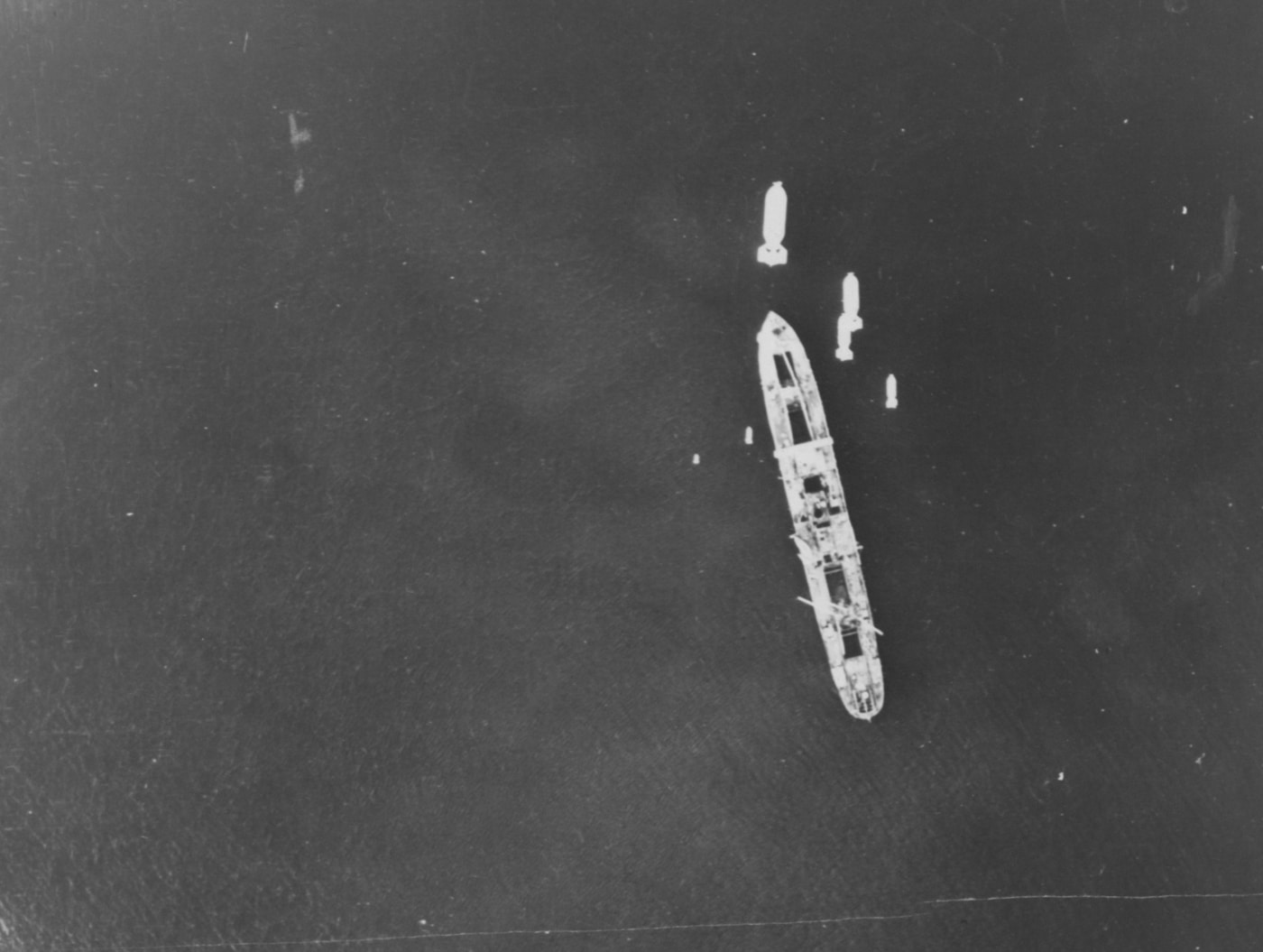

From mid-1942 through early 1943, the Aleutian Campaign was primarily an air and sea battle. American and Canadian warships tangled with Japanese vessels up and down the island chain and at spots in the Bering Sea. Most of the early American and Canadian response to Japanese effrontery in the Aleutians involved air attacks. Fighters and bombers operating from Alaskan bases often missed opportunities for massed strikes due to two major problems that persisted throughout the Aleutians Campaign: weather and distance.

Only heavy bombers of the U.S. 11th Air Force and RCAF’S No. 8 Bomber-Reconnaissance Command had the fuel capacity to reach Aleutian targets and return to Alaskan bases, so Allied forces embarked on operations to establish expeditionary airfields on flyspeck islands closer to Kiska and Attu, which would bring fighter aircraft into the battle.

Despite Herculean efforts by Army engineers and Navy Seabees, it was a tough proposition. Most of the smaller islands in the Aleutians chain were mountainous and covered year-round with muskeg, a sort of glutinous volcanic ash ground layer that often hid three feet or more of subsurface water. Heavy equipment often sunk to axles, and the going was excruciatingly slow.

The Air Battle

Alaskan fog, thick, impenetrable and consistently present over the Aleutians, gave aviators on both sides fits. Targets were often obscured, and operational ceilings were often so low that aircraft became easy pickings for shipboard or ground-based, anti-aircraft gunners.

As winter steadily approached, things just got worse for aviators who had to constantly battle icing as well as unpredictable, treacherous windstorms known locally as williwaws, with wind speeds up to 140 mph. It quickly became clear that despite best efforts by American and Canadian aircrews, the battle for the Aleutians would inevitably involve major ground operations.

The air basing situation improved slightly when U.S. forces sent a reconnaissance force of Alaska Scouts onto Adak, some 100 miles east of Kiska. They found that island surprisingly unoccupied. Engineers were rapidly dispatched and, in three weeks, they established an operational fighter airbase. Heavy bombers from the 11th Air Force and RCAF Bomber Command could now strike Japanese targets with fighter escort. They staged what became known among airmen as The Kiska Blitz.

With Allied airstrikes increasing in tempo and inflicted damage, Japanese ground forces were still optimistic that weather and terrain would save them from an Allied onslaught. They would be reinforced as time and opportunity to avoid Allied air and sea patrols allowed, which was not very often.

Plans to increase Japanese forces in the Aleutians to as many as 7,500 by March 1943 were directed but carried out piecemeal as an increasingly tight stranglehold by Allied warships made such efforts spotty at best. At this point, Japanese forces on Kiska and Attu had grown to include three additional infantry battalions, a mountain artillery battalion, an AA unit, and a company of combat engineers.

Planning Operation Landcrab

Meanwhile, General Buckner was bulking up his forces in the Alaskan Defense Command to get on Operation Landcrab, designed to oust all Japanese forces from their westernmost base at Attu. As a precursor to that full-scale offensive, an American force of 2,000 soldiers from the Alaskan Defense Command (primarily troops from the US 4th Infantry with attached engineers) landed on Amchitka Island just 50 miles from Kiska. They rapidly began constructing an airfield that would put Japanese holdings in the Kuriles at risk.

Coupled with stiffening combat in other theaters, optimism in Tokyo regarding their forces in the Aleutians was fading rapidly. Still the IJA 5th Fleet kept trying to save some of their soldiers in the Aleutians. They attempted to evacuate some garrison troops by submarine, but it was a slow and dangerous proposition at best.

As an order of battle involving Canadian and American forces for Operation Landcrab was being mustered, action shifted to war at sea. Despite American and Canadian warships combing the waters along the Aleutian island chain, Japanese Navy vessels were still trying to support their garrison forces on Attu and Kiska. From the Allied perspective, that had to cease in order to prevent Operation Landcrab from becoming a long, bloody battle of attrition.

Battle of the Komandorski Islands Dooms Japanese Troops

It was while attempting to cut off Japanese naval efforts to resupply their Aleutian islands garrisons that one of history’s last large scale surface fleet combat actions occurred. The IJN 5th Fleet — at this point minus the carriers and built around four cruisers and five destroyers — was escorting a convoy of auxiliary vessels when it was intercepted by the American Navy’s Task Group 16.6 (two cruisers and four destroyers) in Japanese waters southeast of the Soviet Komandorski Islands.

The American sailors found themselves outnumbered and a long way from any help. What followed as both fleets engaged was a wild, five-hour running battle involving guns, torpedoes and even aerial bombs from USAAF bombers trying to intervene at the last moment — to no avail. The heavy cruiser Salt Lake City and IJN cruiser Nachi were both badly damaged and nearly sunk before both sides limped away toward friendly ports.

The sea fight known as the Battle of Komandorski Island finally convinced the Japanese that further expenditure to maintain their foothold in the Aleutians was fruitless. Lacking an easy way to evacuate and redeploy, they would have to stand and fight.

Reaching essentially the same conclusions, General Buckner pulled the trigger on Operation Landcrab. Allied forces in the American Theater had been significantly reinforced to more than 71,000 troops, and Admiral Nimitz, in concert with the Western Defense Command, agreed they were strong enough to stage a westward advance down the Aleutian chain toward Kiska and Attu. It was time to bring on the infantry.

Meanwhile in Tokyo, IJA planners were dealing with more pressing matters elsewhere in the Pacific. An edict reached the 5th Fleet when it became obvious that the Allies were poised to strike at Attu and Kiska. Evacuation efforts would continue, but for the most part, Japanese forces would have to hold and carry out preparations for the inevitable Allied ground offensive.

Fatalistic as that seemed, it was about all the Japanese hanging precariously out in the cold of the Aleutians could do.

The Ground Campaign Commences

Operation Landcrab’s objective was fog-shrouded Attu, just 35 miles long by 15 miles wide, and a confusing mess of waterlogged valleys intersected by swift-flowing creeks and steep ravines.

Plans called for a two-prong assault by a Northern Force and a Southern Force, both compiled from elements of the US 7th Infantry Division led by Army Major General Albert Brown. His line combat outfits were the 17th and 32nd Infantry, organized as Regimental Combat teams, each RCT containing three infantry battalions. Included was a Provisional Scout Battalion, a Coast Artillery (anti-aircraft) unit, and a battalion of combat engineers.

The 7th Infantry Division was a puzzling choice for the Aleutians Campaign. The unit was originally organized and trained as a motorized infantry command destined for deployment to combat in North Africa. When things heated up in the Alaskan territory, the 7th Division was stripped of its vehicles and began to train at Ft. Ord, California under U.S. Marine amphibious warfare experts and veterans with experience in Alaskan operations. It was a capable outfit, if a bit disgruntled and confused by the switch in tactics and training.

General Brown’s intelligence was thin and spotty, and his scheme of maneuver was mainly developed from a single U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey map, which was all that was available prior to the 11 May scheduled landing date. He had little information on the size and strength of his enemy on Attu. What he did know for certain was that his landing areas would be tight. Just five percent of Attu’s rocky coastline was actually capable of accommodating landing craft.

Additionally, he knew it was bound to be a miserable fight in damp, dreary weather where temperatures often fell to only 10 degrees Fahrenheit. His troops were woefully unprepared to fight in such conditions over terrain that mostly consisted of moss, tundra and low shrubs below several 3,000-ft., snow-covered mountains.

For some unfathomable reason, the 7th Division had not been issued with winter uniforms or boots. They would have to fight in light field jackets, leather boots and personal combat gear that was completely unsuitable for arctic conditions.

When word of the potential offensive reached Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki, the Japanese commander on Attu knew what had to be done with his half-starved force of just over 2.500 troops. He sent the 83rd Infantry Battalion to oppose north side landings at Holtz Bay and his 303rd Infantry Battalion to face the enemy coming ashore to the south in the Massacre Bay/Chichagof Harbor area. Col. Yamasaki knew he was outmanned and outgunned, so he opted not to fight on the landing beaches.

He emplaced his firepower, including 75mm AA guns, pack howitzers, heavy machine guns and mortars, in well-sited positions atop steep ridges and above the fog line. This would give the Japanese defenders fields of enfilading and plunging fire on their attackers.

For much of the ensuing fight on Attu, the Japanese could see the Americans below their redoubts, while the Americans often found themselves under fire, staring up at an invisible enemy shrouded by fog.

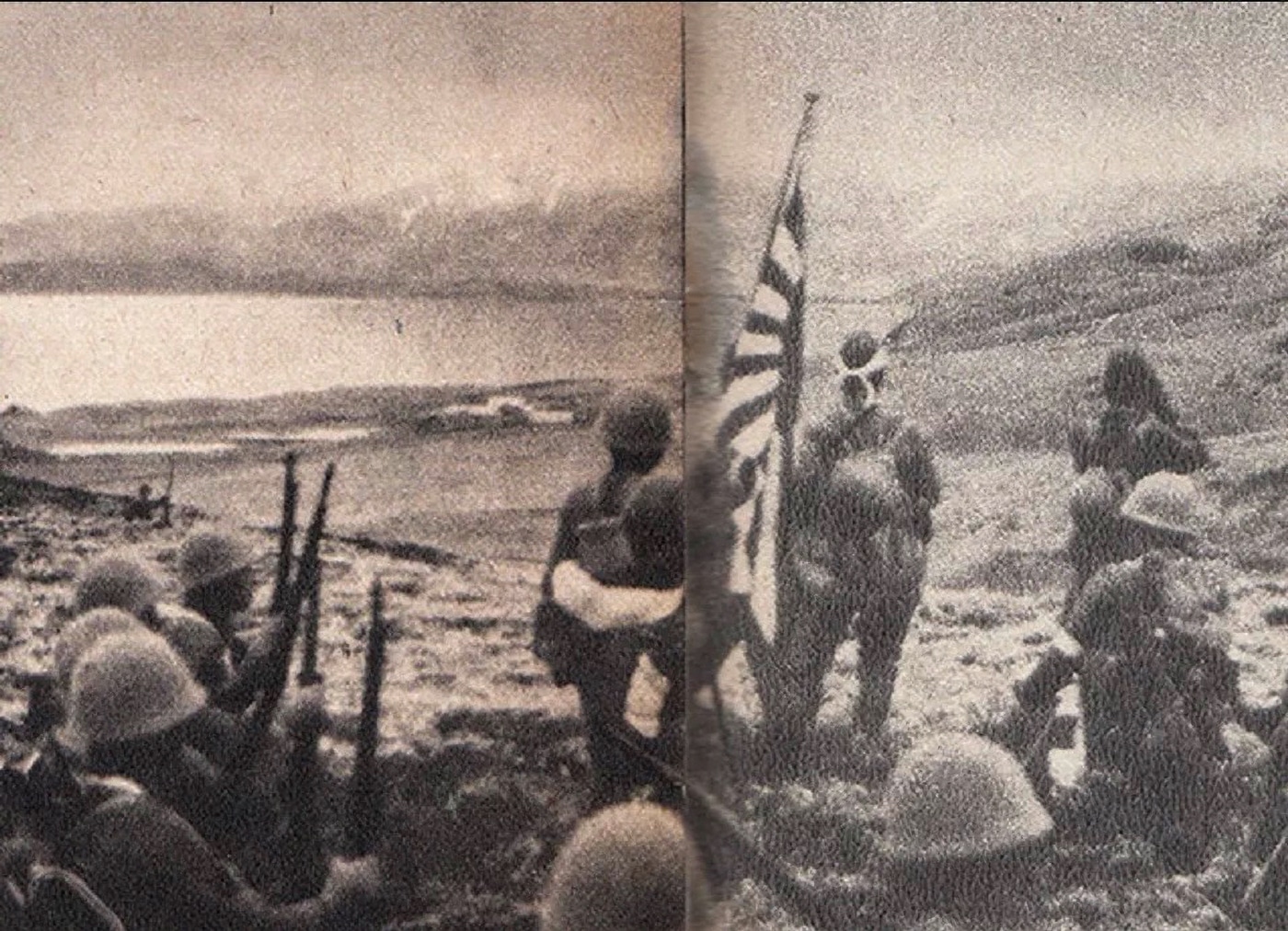

The fight for Attu commenced on the afternoon of 11 May, when infantry combat formations began streaming ashore following Scout and Reconnaissance troops landed from submarines and destroyers in pre-dawn darkness.

The landing of battalion combat teams began maneuvers from north and south, which continued for the next four days and was hampered by weather, high seas and poor communications. High-altitude atmospherics badly hindered radio transmissions, while persistent fog frustrated visual signals, couriers and aircraft trying to direct lost formations.

Attu was proving to be a defender’s dream. General Brown’s infantry was being channeled through valleys and draws overlooked by Japanese defenders hiding in the fog line on the high ground. Their positions created kill sacks on the ground below and prevented any flanking maneuvers by American infantry.

For the attackers, it was mostly a matter of grinding uphill advances into the teeth of Japanese fire. What close-quarters combat occurred in those snowy, frigid high levels was mostly hand-to-hand and exceedingly brutal. American casualties due to frostbite and trench foot mounted as small units of stubborn Japanese defenders were able to frustrate much larger attacking forces.

Convinced that General Brown had lost momentum and was settling for a stalemate after just one week of combat on Attu, Rear Admiral Thomas Kincaid, a battle-tested sailor and Brown’s superior commanding from offshore, relieved Brown and replaced him with Army Brigadier General Eugene Landrum, an Alaka veteran.

Landrum didn’t — really couldn’t — change much on the tactical level. He let his troops rest until 18 May and then began an all-out push toward Chichagof Harbor, which was the assault force’s final objective. He massed forces from the two fronts on Attu and forged ahead over a four-mile front toward the harbor.

Initially, it was the same series of grinding frontal assaults, but Landrum crucially chose to conquer the high ridges and crests surrounding his route before maneuvering across the low ground. When they encountered stiff enemy resistance in these fog-shrouded redoubts, Landrum had his troops drag 37mm AT guns up the mountainsides and use direct fire to dislodge defenders.

By late May, Americans held most of the vital high ground on Attu and were reorganizing with engineers ashore, building roads through the tundra to allow rapid resupply and evacuation of casualties. The reserve 4th Infantry had been brought ashore to reinforce the final push.

By the end of May, with Allied forces overlooking Chichagof Harbor, it appeared to be all over but the casualty counting on Attu. Still, Colonel Yamasaki had one last card to play. With American forces fixated on Chichagof Harbor below the high ground they recently conquered, Yamasaki sensed that they might be vulnerable to an attack from the rear.

He chose to make that final desperate banzai charge with 600 or so survivors at an insignificant little hill occupied by the 50th Combat Engineer Battalion in pre-dawn darkness of 29 May. It was a brutal, suicidal move of the sort that would prove to be typical of hard-pressed Japanese defenders later in the war.

They attacked in continuous waves against fierce American resistance in the Battle of Engineer Hill until dawn broke, and bloodied Japanese attackers finally realized the cause was lost at the cost of half of their attacking force. Some 300 survivors melted back into the hinterlands. Most of them committed suicide in the following days.

The American forces swarmed down to take Chichagof Harbor and the battle for Attu was over. It had been an old-fashioned teeth-and-nails fight featuring head-on infantry assaults and artillery duels. The butcher’s bill was stiff.

Victors counted 2,351 dead Japanese on the island. Only 28 of them were captured. American forces in the Attu battle suffered 549 killed in action, plus 1,148 wounded — not counting some 1,200 weather-related casualties.

Admiral Kincaid and General Buckner rested their troops and assembled more while they continued to blast the Japanese garrison on Kiska with airstrikes and naval gunfire. Fortunately for the Japanese garrison on that island, just 180 miles east of Attu, the bunkers, caves and defensive fortifications built when airfield construction efforts failed kept casualties to a minimum.

With Attu and other island airfields in hand and operating at high tempo, the Allied Alaskan command improved their positions, carved more support facilities out of the tundra, and commenced air strikes on Japanese holdings in the Kuriles. They also tightened the naval blockade around Kiska, prior to commencing Operation Cottage — the assault on the island scheduled for mid-August.

The Japanese 5th Fleet, still operating in northwestern Pacific waters, understood that the situation facing the troops on Kiska was now desperate. If they were to be saved for further service in the war, a bold plan was needed. That plan was developed by Japanese Vice Admiral Shiro Kawase, who believed he could sneak some of his heavy warships into Kiska at night under cover of dense fog.

He pulled off that desperate gamble on the night of 28 July with two light cruisers and nine destroyers that managed to evade the Allied naval blockade, and evacuated more than 5,000 men off Kiska in less than one hour.

Allied intelligence didn’t know the details about what happened with Japanese forces on Kiska, but they knew something significant had changed while plans for Operation Cottage were being finalized. There were some reliable reports that Kiska had been evacuated. Radio intercepts and photo reconnaissance missions seemed to show an empty island. Some analysts insisted that it simply meant that the Japanese on Kiska were lying low, prepping for an invasion, or that they had moved all their forces to defensive positions on the island’s high ground, as was the case on Attu.

Just prior to the scheduled D-Day for Operation Cottage on 15 August, Captain George Ruddell, in a bold reconnaissance mission, landed a flight of P-40 Warhawks on Kiska with no resistance from Japanese defenders. He walked around for an hour, taking pictures of abandoned positions and then flew off to report his findings.

Admiral Kincaid saw the photos and heard the flyers’ reports but decided against launching a ground reconnaissance mission to confirm them. Operation Cottage would commence as scheduled. The Admiral felt it would be good training if nothing else.

The Final Stages

The Kiska operation was commanded by U.S. Army Major General Charles Corlett, who would lead a multi-national American and Canadian force in the seizure of Kiska. The American contingent included elements of the now-seasoned US 7th Infantry Division and some newly raised supporting formations.

Scheduled to land in successive waves on Kiska were the 4th, 17th 53rd and 184th Infantry Regiments, plus the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, which was specifically designed to target Japanese forces on the island’s 4,000-ft. Kiska Volcano.

Making their operational debut would be the U.S.-Canadian 1st Special Service Force Brigade. This elite American and Canadian commando outfit, which became known as the Devil’s Brigade, was raised and trained in Montana in 1942. Operation Cottage would be their first deployment.

The Canadian Greenlight Force for Operation Cottage was similarly strong and bulked up for combat on Kiska. Combat formations scheduled to land on the island alongside the Americans included units from the 6th Canadian Infantry Division. They were organized as the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade and included elements of the Canadian Fusiliers (City of London) Regiment, 1st Battalion of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Rocky Mountain Rangers and Le Regiment de Hull.

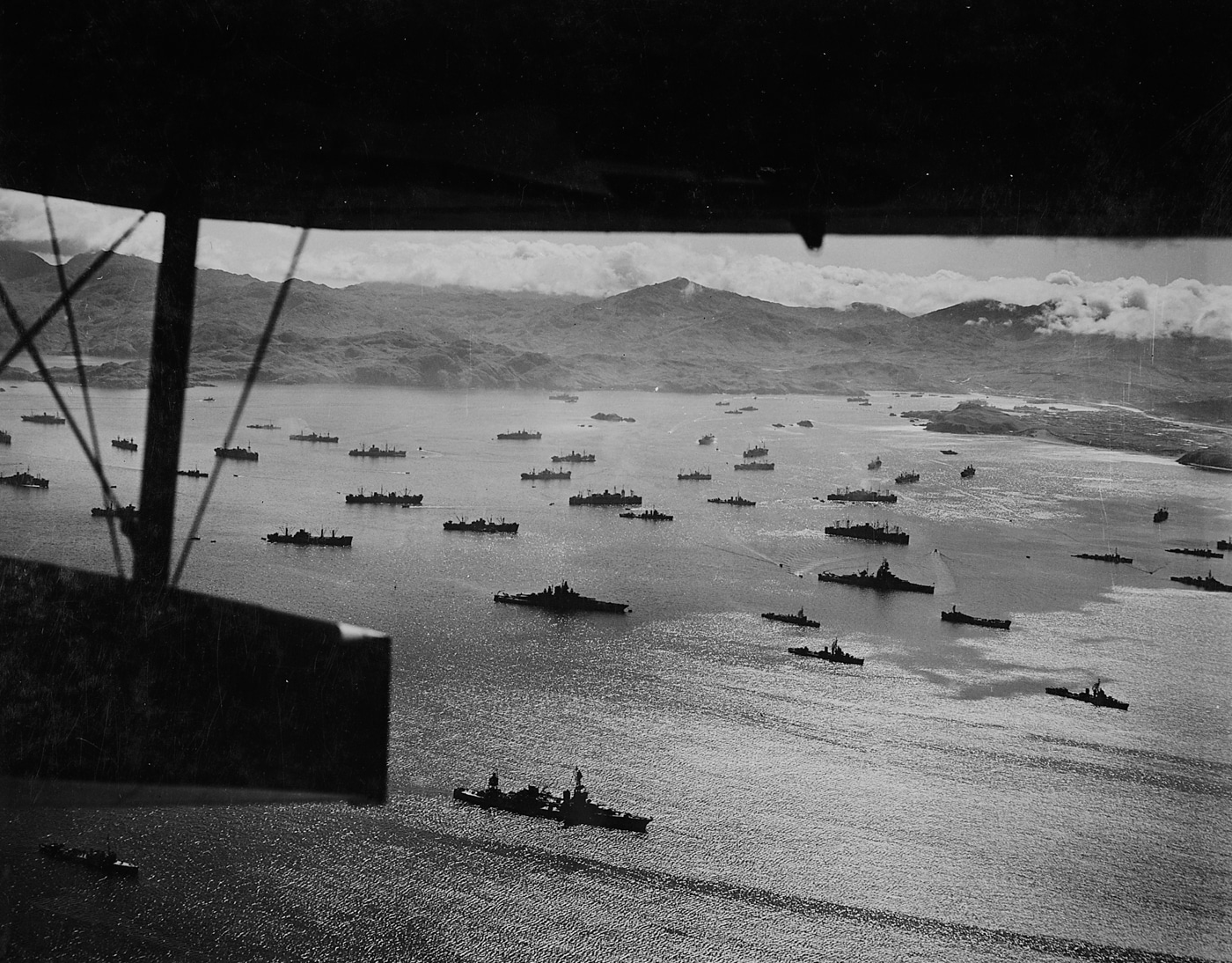

In all, the Kiska assault force numbered nearly 35,000 ground troops covered by more than 100 bombers and nearly as many fighter aircraft. Offshore would be two battleships, two cruisers, 19 destroyers, plus a large flotilla of amphibs and auxiliaries.

Having been mauled in the Attu operation, the Allied forces had come fully manned and prepared to play hardball this time. The stage was set for what was to become one of the war’s biggest anti-climaxes.

On D-Day 15 August, Kiska’s entire stretch of 22 miles long and four miles wide was blanketed in wet mist and low fog. Pre-invasion air strikes and aerial reconnaissance efforts were nearly useless, and the planned naval bombardments from a large invasion fleet were essentially blind shots with no corrections on invisible targets available.

Despite all that, the first assault waves came ashore led by the Devil’s Brigade troops of the 1st SSF, followed by elements of the 17th RCT and 87th Mountain Infantry. Initial reports from the landing forces indicated that Kiska had been abandoned, but they were ordered to make sure of that.

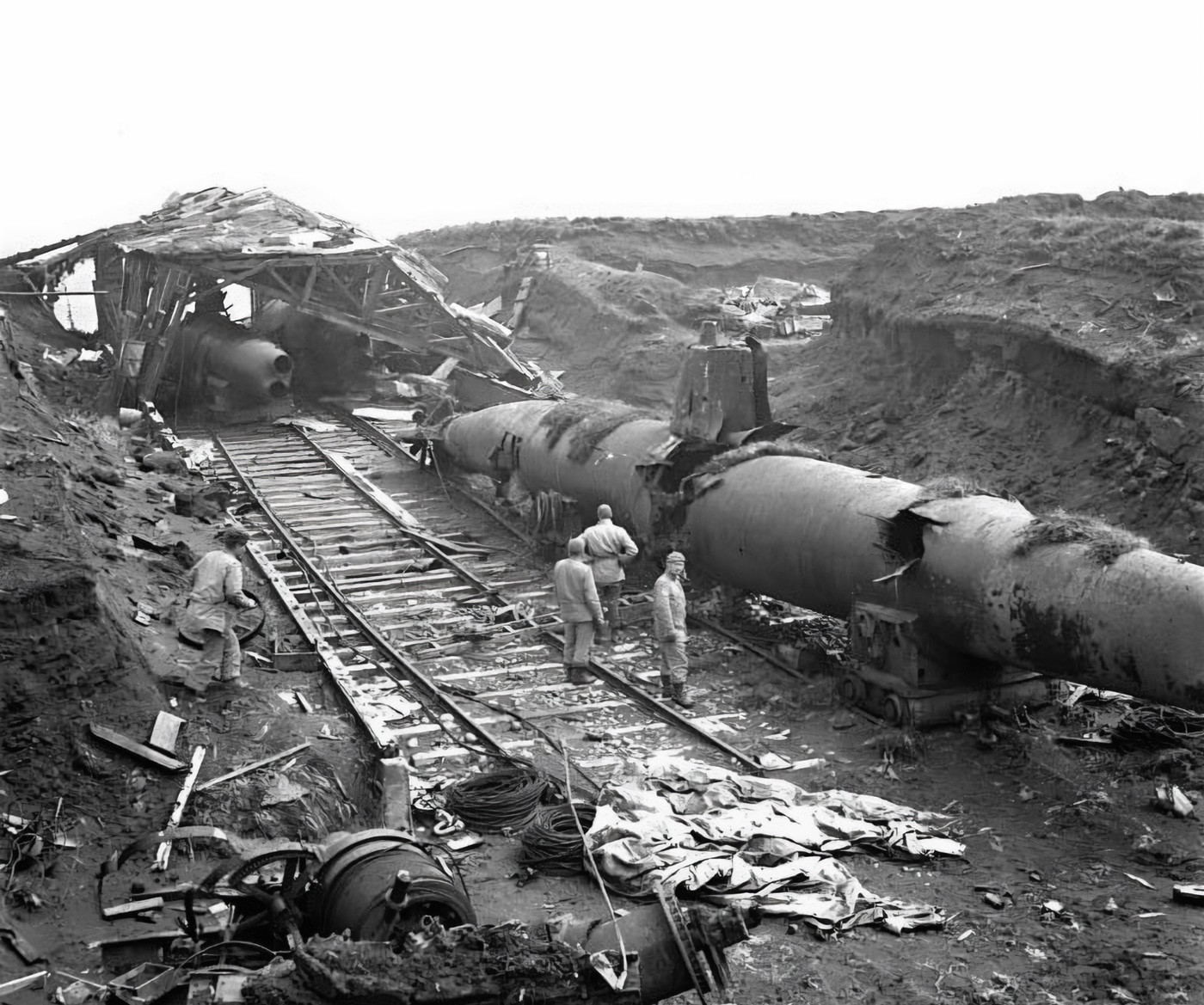

With the Canadians waiting offshore, the Americans pressed on through icy rain and disorienting fog, searching for any Japanese left on the island. They were all cocked and locked, itching for a fight, but all they found were abandoned bunkers and mocking graffiti left by the Japanese. There were a few abandoned heavy weapons and some wrecked aircraft, but no live Japanese on Kiska.

There were, however, some mines and boobytraps left behind, which caused casualties as the American forces searched the island. More significantly, there were several incidents of friendly fire by units confused by near-zero visibility and suffering from combat jitters. After two days of banging around blindly in the fog and shooting mostly at each other, the Allied commanders called it off and began to recover the landing forces.

Some of the invasion fleet was ordered to sail for Adak and, in the midst of that movement, the U.S. destroyer Abner Hill hit a mine left in the harbor, which killed 70 sailors and wounded 47 more. That incident brought the casualty count for the attack on an abandoned island to 313, including 92 killed and 221 wounded by left-behind mines and booby traps or friendly fire incidents.

Obviously, there were no Japanese casualties in the Kiska operation, which quickly became known far and wide as a JANFU — Joint Army-Navy F$%k Up.

Conclusion

In the overview, Allied operations in the Aleutians Campaign were a strategic dead-end. The American and Canadian forces had retaken positions that gave them stepping stones to nowhere, but they did learn some valuable lessons about fighting the Japanese.

During the Attu fighting, defenders fought nearly to the last man. In later campaigns in the South Pacific and elsewhere, that proved to be the nature of Japanese warfighting. In campaigns from 1943 onward, nearly every assault on Japanese-held islands was fought to the last man against an enemy that was tactically proficient in defensive fortification as well as stubborn and tenacious in combat.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply