“The soldier fighting in bitter winter weather cannot pull the trigger of his rifle with frozen fingers, cannot march on frozen feet, and cannot survive without blankets or sleeping bags and layers of warm clothing.”

From “Outfitting the soldier: Quartermaster Supply in the ETO” (1948)

When I was growing up in Western New York, I walked to school. I’d like to say “uphill, both ways”, but it only felt like that. It was worse in the winter, and while I trudged through the snow during the mid-1970s, many weather forecasters were proclaiming the coming of a second ice age. Once, during the nightly news, I agreed out loud with a local meteorologist who made one of those ice age assessments.

My father gave me a hard look across the dinner table, and he spoke with a commanding voice he acquired as an infantry sergeant during World War II. “You don’t know a damned thing about being cold, or hungry, or tired. You sleep in a warm bed, you eat hot meals, and nobody’s shot at you.” He was right, and I shut up about it.

About 25 years later, I was in his office talking with him about his service with the 8th Infantry Division during WWII. He saw more than his share of combat, but two hardships stayed fresh in his mind: the battle of the Hurtgen Forest, and the bitter winter of December 1944 through March 1945. His language was often rough, so I can’t repeat it all here, but he concluded with: “Leave it to your dear old dad to go camping in one of the coldest European winters on record, where Old Man Winter was as tough an opponent as the Krauts. We used to kid each other and say: “What’re you crying about…you’re getting paid, aren’t you?”

It didn’t take too long to find out why he and many former G.I.s had no patience for civilians complaining that they were cold or hungry. For American and German troops facing each other in Western Europe during that winter, the war was very much a competition of suffering. American ingenuity and toughness kept the G.I.s in the fight, and as the snow and the Germans melted away, they owned the battlefield. But there were no easy days on the road to victory.

Failure Was Not an Option

“Outfitting the soldier”, the report of the U.S. Army Quartermaster about logistics and supply in the ETO, is an interesting, detailed, and surprisingly honest history. For example: “Supply of clothing and individual equipment to the soldier who fought in the European Theater is shot with mistakes in planning and execution. Yet the outfitting of the men who were able to crush the greatest military machine of all times could not have totally failed.”

This is a fair and accurate assessment. Ultimately, American (and all Allied) supply organizations faced a wide range of challenges. One of the biggest was a significant underestimation of the impact of a harsh winter, and this had a profound effect on the equipment available to the combat troops.

The Winter Uniform

In May (1944) the Plans and Training Division and the Supply Division agreed that the winter uniform should consist of service shoes, light woolen socks, woolen underwear, flannel shirt, woolen trousers, olive-drab field jacket, and overcoat.

The Quartermaster General agreed with the basic items selected, but believed that the use of the overcoat would “have extremely serious and detrimental results on the efficiency of the combat soldier. It should be replaced by the M-1943 field jacket and high-necked sweater.”

This combination was not only warmer than the overcoat but lighter in weight. The proposed uniform weighed 21 ¼ pounds. If the jacket and sweater were used, the weight would be reduced to 18 ½ pounds. The Theater Commander subsequently agreed to accept the high-necked sweater. The overcoat would not be eliminated, however, and would be issued to all troops except parachutists, who would be the only troops to receive the M-1943 field jacket.

Distribution Problems

Cold weather came to northern Europe in the early fall of 1944. On 7 September, the day the Third United States Army crossed the Moselle River, the Chief Quartermaster wrote the Commanding General of the Communications Zone as follows: “Cold weather is here. Fighting forces are demanding heavy clothing and additional blankets which the assault troops and a substantial percentage of the entire force did not bring to the Continent. Issues must be completed by 1 October if the fighting efficiency of the troops is to be maintained.”

The Winterizing Program

The distribution of warm clothing to the armies began at once. On 13 October, the Chief Quartermaster announced that the so-called “winterizing program” was completed. “I say so-called winterizing,” he wrote, “because it does not mean that all the winter items that are to be provided in this Theater have been furnished to the armies.”

It merely meant that all the warm garments and items of winter equipment that the Quartermaster Service had available in the European Theater had been given to the combat forces. The troops of the First Army entering Aachen and the troops of the Third Army at Nancy and Metz received more than 6,500 long tons of clothing and equipment

Unexpected Wear and Tear

Equipment that had been expected to last a year wore out in a few months. The War Department expected a pair of socks to last about four months under normal combat conditions. Experience on the Continent proved they wore out in about 15 days. Woolen undershirts that had been expected to last six months wore out in four and half months. Overcoats expected to last 18 months had to be replaced in nine months.

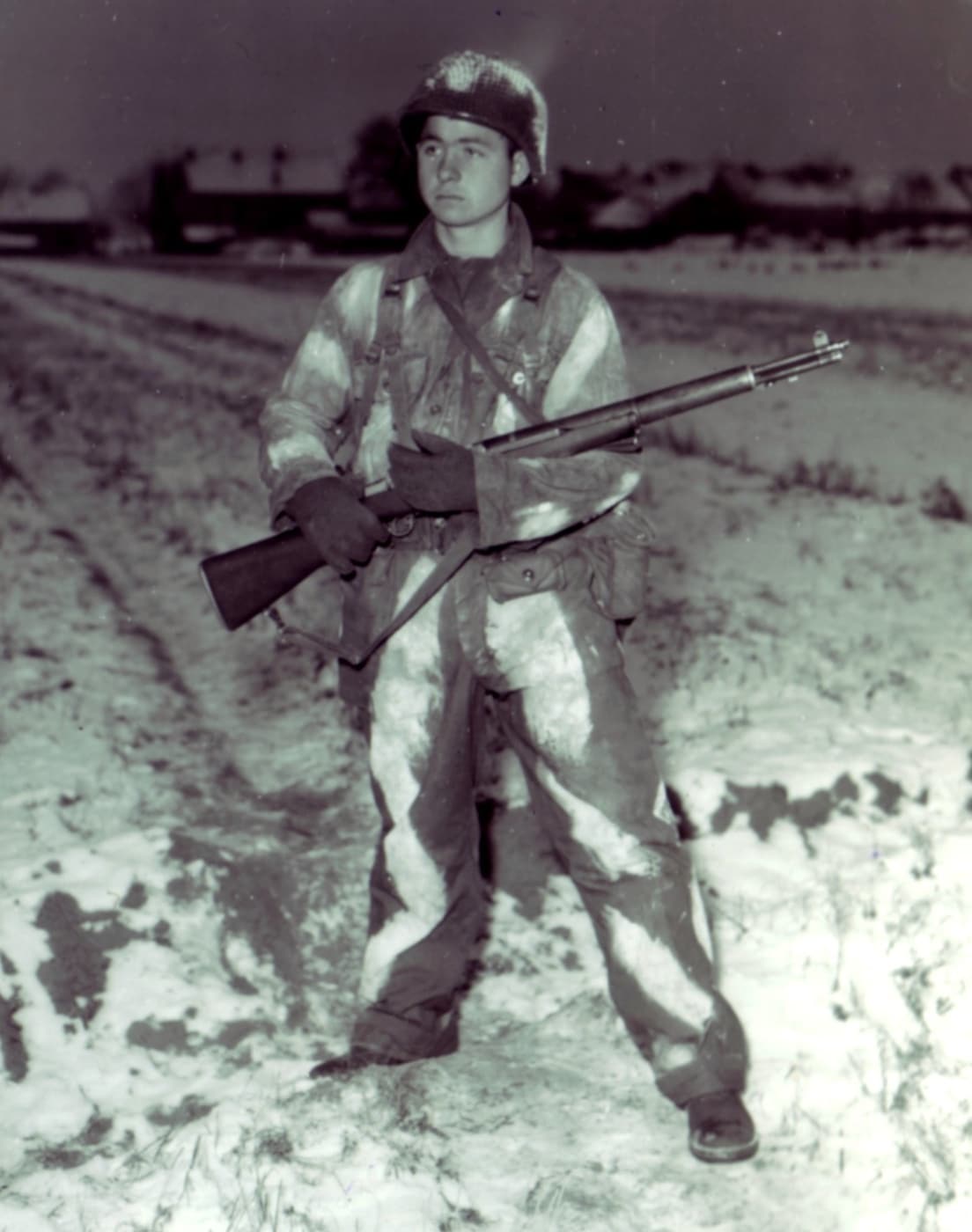

During the Belgian Bulge in the Bastogne sector and at Malmedy, troops were keeping warm as best they could. Warm uniforms of all kinds were being improvised. Riflemen were wearing combat boots, two pairs of woolen socks, one pair of woolen drawers, two woolen undershirts, one pair of woolen trousers, a flannel or woolen shirt, a high-necked sweater, woolen gloves with leather palms, a field jacket of any variety, a muffler, steel helmet and a wool-knit cap.

Artillery units were wearing the same woolen uniform and an outer layer of herringbone twill. Tank crews were wearing service shoes, overshoes, cotton and woolen under-clothing, woolen shirts and trousers, two or three pairs of socks, winter combat jackets, leather glove shells, and woolen glove inserts.

Trigger Mittens

A limited distribution of trigger-finger mittens was made in January 1945. Troops of the 17th Airborne Division were pleased with the item. The division quartermaster believed the mitten should be an essential part of the winter combat uniform. Even though it cut down the full use of the fingers, its warmth and protection were sufficient compensation.

Combat Boots and Trench Foot

Most men had been fitted during the summer in United Kingdom or at reception centers in the United States, when they had worn light woolen or cotton socks. The American soldier’s desire for a snug, well-fitting shoe was a national characteristic. The boots and shoes, therefore, were too small and too narrow when worn over several pairs of heavy woolen socks.

Complaints grew louder as increased numbers of combat boots reached the front lines. The boots leaked and were cold, even after constant dubbing. Troops provided with flesh-side-out service shoes made the same complaint. Though smooth-surfaced leather was preferred, all troops wanted the combat boot because it did away with leggings.

Trench foot is a term used by the Medical Department for injury to feet caused by prolonged exposure to cold at temperatures just above freezing. It is similar to frostbite, which is caused by exposure in below-freezing temperatures. In the French Army during WWI, trench foot amounted to 3.02 percent of the total number of battle casualties. During the period October 1944 to April 1945, 46,107 United States soldiers in Europe were hospitalized because of it. This figure equaled the troop strength of three combat divisions and was 9.25 percent of the total number of casualties during the entire Continental campaign.

Trench foot emerged among the combat forces like a contagious disease. The first wave began in November and lasted until the second week in December. The second wave began during the German counterattack in the Ardennes. The third, which was really a wave of frostbite, broke out early in January 1945. Trench foot was most common in infantry divisions where soldiers had been living in the wet and cold without the opportunity to change shoes and socks regularly. Trench foot was attributed to five causes: improper care of the feet, the wrong kind of footgear, inadequate winter clothing, failure to rotate troops, and cold and wet weather.

When two or three pairs of socks were worn, combat boots and service shoes were too tight and interfered with circulation. Large-size boots and shoes could not be delivered immediately. Heavy woolen and ski socks were available only in limited numbers during the trench foot season. Troops were instructed to change their socks daily. Yet socks could not be dried overnight, and a change of socks could not be provided. Overshoes were not the answer — they were tiring on long marches; they interfered with proper ventilation; and they were not available in large enough sizes.

Some troops discarded boots or shoes and instead put several thicknesses of blanket padding inside their overshoes. “Shoepacs”, although not entirely satisfactory, were the best footgear provided in the European Theater. Sufficient amounts, however, were never available to equip all combat troops. Because the first models did not have heels high enough to provide proper arch support, troops were reluctant to accept them. The War Department corrected the design, but the improved models did not become available in time to make a complete issue to combat troops before the spring of 1945.

Recommendations for Improvements

G.I.s were interviewed about their winter gear needs, and while these were carefully recorded and given credence, the war would be over before any real improvements could be made. On January 28, 1945, Infantry Observer Colonel Albert G. Wing documented the following “Proposed Changes in Organization and Equipment” report on G.I. snow equipment:

“Present combat shoes are not waterproof and are too cold for winter wear, when supplemented by the overshoe, the soldier’s agility is materially impeded.”

“The wool issue glove is not sufficient protection on very cold days, nor will it stand much wear.”

“Consideration should be given to a felt-lined boot, possibly with a rubber foot and leather top (like the Maine hunting boot) for winter wear by combat troops.”

“The most serviceable and warm uniform yet designed for front line units is the two-piece combat suit issued to armored units. The material of which it is made withstands a great deal of wear and tear, is water repellent, windproof, warm, and comfortable. Until something better is designed, this suit should be the winter uniform for front line units.”

G.I. Improvisations

“Yank Magazine”, March 2, 1945, edition. In an article by Sgt. Ed Cunningham, men of the 83rd Infantry Division talked candidly about their winter war improvisations during the Battle of the Bulge.

Frozen weapons were one of the most dangerous effects of the winter warfare in the Ardennes. Automatic weapons were the chief concern, although some trouble was experienced with M1 rifles and carbines. Small arms had to be cleaned twice daily, because of the snow, and none of the larger guns could be left unused for any length of time without freezing up.

“The M1s were okay if we kept them clean and dry,” said Tech. Sgt. Albert Runge, a platoon sergeant from Boston, Mass. “You had to be careful not to leave any oil on them or they would freeze up and get pretty stiff. But you could usually work it out quickly by pulling the bolt back and forth a few times. Sometimes the carbines got stiff and wouldn’t feed right, but you could always work that out, too.”

“The BARs gave us the most trouble,” Runge said. “They froze up easily when not in use. Ice formed in the chamber and stopped the bullet from going all the way in, besides retarding the movement of the bolt. We thawed them out by cupping our hands over the chamber or holding a heat ration near it until it let loose. Most of the automatic weapons were okay too, after you worked them a few times manually, and we never did have any trouble with ‘grease guns.’”

Some other outfits reported that the lubricants in their light machine guns and anti-tank guns froze. Heat tablets were ignited to thaw out the machine guns, which couldn’t be cocked. But blow torches were needed before the anti-tank guns were put back into firing condition.

During the fighting at Petit Langlier, Pvt. Joseph Hampton found himself in a spot where he had no time to fool around with the above methods. Just as his outfit started into action, Hampton found that ice had formed in the chamber of his M1 Garand rifle. With no time to waste, Hampton thought and acted fast. He urinated into the chamber, providing sufficient heat to thaw it out. Not five minutes later, he killed a German with his now well-functioning rifle. Hampton’s company commander vouches for that story.

Fighting Winter Itself

“Some of the men took off their overshoes and warmed their feet by holding them near burning G.I. heat rations (fuel tablets) in their foxholes,” McQuinn said. “Others used waxed K-ration boxes, which burn with very little smoke but a good flame. Both G.I. heat and K-ration boxes are also fine for drying your socks or gloves. I also used straw inside my overshoes to keep my feet warm while we were marching. Some of our other men used newspapers or wrapped their feet with strips of blankets or old cloth.”

McQuinn’s company commander, Capt. Robert F. Windsor, had another angle on keeping feet warm. “We found our feet stayed warmer if we didn’t wear leggings,” Capt. Windsor explained. “When they get wet from snow and then freeze, leggings tighten up on your legs and stop the flow of blood to your feet. That’s true also of cloth overshoes, which are tight fitting. When snug-fitting overshoes get wet and freeze, they bind your legs. It looks to me like overshoes should be issued two or three sizes larger than shoes to prevent that.”

“Another ‘must’ in this kind of weather,” Capt. Windsor continued, “is to have the men remove their overshoes at night when it’s possible. Otherwise, these cloth arctics sweat inside, and that makes the feet cold. Of course, the best deal is to have a drying tent set up so you can pull men out of the line occasionally and let them get thoroughly dried out and warm.”

The drying tent to which Capt. Windsor referred is nothing more than a pyramidal tent set up in a covered location several hundred yards behind the front, with a G.I. stove inside to provide heat. There an average of seven men at a time can dry their clothes and warm themselves before returning to their foxholes. This procedure takes from 45 minutes to two hours, depending on how wet the men’s clothes are. All the front-line outfits in the 83rd Division used this method.

Web equipment was a problem. It froze solidly on cold nights and had to be beaten against a tree in the morning to make it pliable enough for use. The standard G.I. gloves also proved unsatisfactory for winter fighting, 83rd Division men reported. When wet, they froze up and prevented the free movement of the fingers. Nor were they very durable, wearing out in a few days under the tough usage they got in the forest fighting. When their gloves wore out, many of the men used spare pairs of socks as substitutes.

The Bitter Winter

This has been a hard winter for much of America. In my part of the world, snow and ice continue to build — it seems like most of it is in my driveway. But even in the middle of my frosty grumbles and gripes, I remember my father’s stories about the bitter winter of 1945. They remind me that wars are fought with strategy and tactics, weapons and logistics, but they are won by the troops that refuse to give up or give in to the enemy or the environment.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply