“We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The Potsdam Declaration, issued on July 26, 1945, and signed by U.S. President Harry S. Truman, United Kingdom Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Chang Kai Shek, President of China.

World War II was coming to an end. The effect of two atomic bombs, at Hiroshima on August 6th, and Nagasaki on August 9th, had seemed to dramatically change the way Japanese leaders viewed their continued resistance. Only days before, surrender seemed a complete impossibility. After the two atomic blasts, surrender appeared to be the only option.

President Truman announced via radio broadcast on August 11, 1945:

“I have received this afternoon a message from the Japanese Government in reply to the message forwarded to that government by the Secretary of State on August 11th. I deem this reply a full acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, which specifies the unconditional surrender of Japan. In the reply, there is no qualification. Arrangements are now being made for the formal signing of the surrender terms at the earliest possible moment. General Douglas MacArthur has been appointed the Supreme Allied Commander to receive the Japanese surrender. Great Britain, Russia and China will be represented by high-ranking officers. Meantime, the Allied armed forces have been ordered to suspend offensive action. The proclamation of VJ Day must await upon the formal signing of these terms by Japan.”

The unconditional surrender terms of the Potsdam Declaration were strict, but simple to understand:

- The elimination “for all time of the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest.”

- The occupation of “points in Japanese territory to be designated by the Allies.”

- That the “Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku, and such minor islands as we determine,” as had been announced in the Cairo Declaration in 1943.

- That “the Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted to return to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives.”

- That “we do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation, but stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners.”

However, the Potsdam Declaration provided the light of democracy at the end of a long and dark tunnel:

- “The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established.”

- “Japan shall be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind, but not those which would enable her to rearm for war. To this end, access to, as distinguished from control of, raw materials shall be permitted. Eventual Japanese participation in world trade relations shall be permitted.”

- “The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established, in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people, a peacefully inclined and responsible government.”

Flight to Unconditional Surrender

After years of brutal combat, coordinating a war-ending surrender was complicated and delicate. The slightest mistake could easily restart the conflict. Even so, the Allies could not waver. The Japanese would surrender unconditionally — and the challenge was to get the authorized representatives of the warring powers together to sign the war-ending legal documents.

General MacArthur decreed that the Japanese delegates would come to him in Manila to sign the surrender agreement. However, the Japanese had no aircraft capable of carrying their delegation from the home islands to the Philippines. After a series of complicated exchanges through diplomatic and military channels, a procedure was agreed upon to bring the Japanese delegation to the U.S.-held island of Ie Shima, located a few miles from the Motobu Peninsula of Okinawa. From there, they would be flown by an American aircraft to meet with MacArthur in Manila.

Bataan-1 and Bataan-2

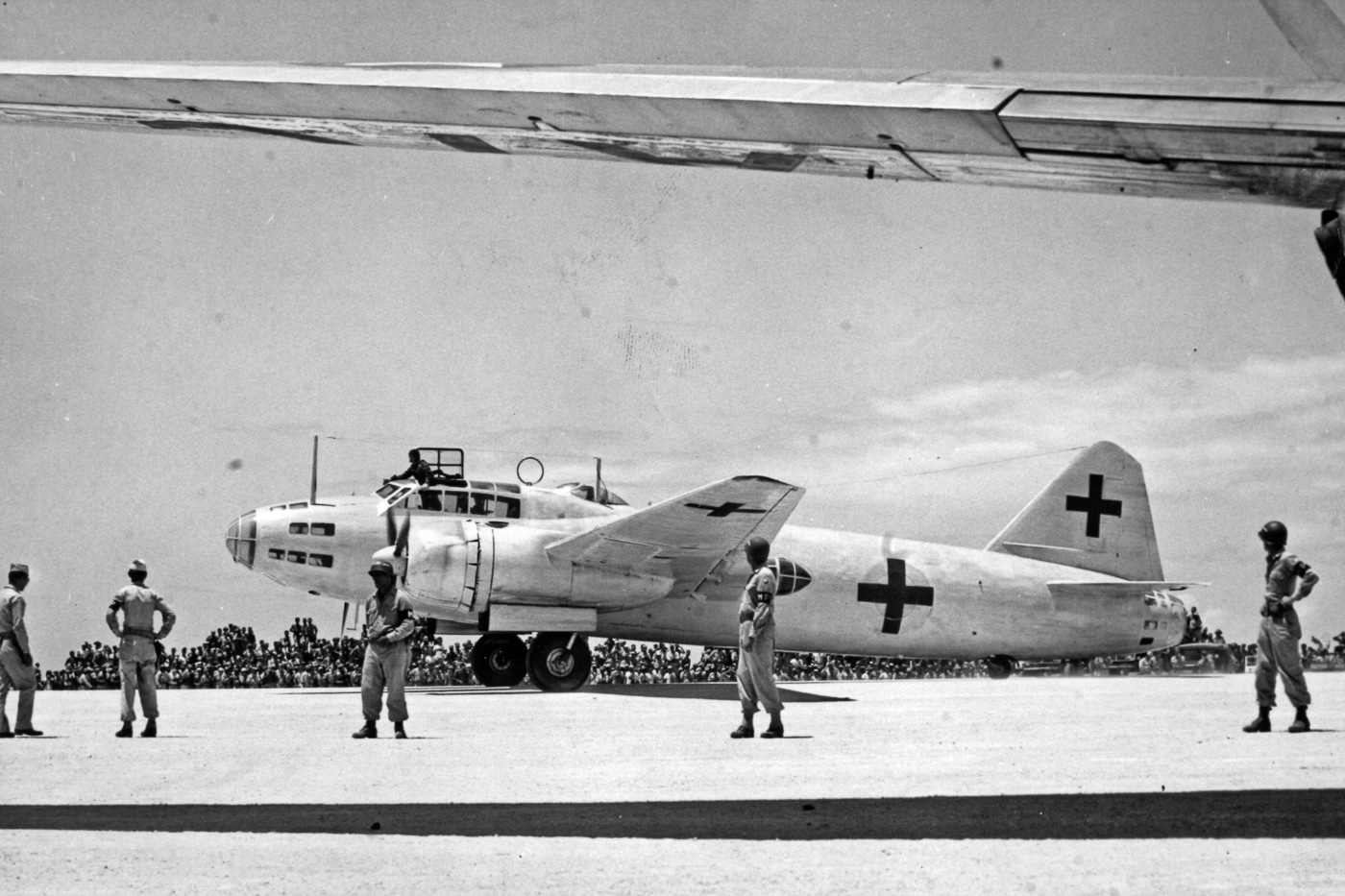

It was decided that the Japanese delegation would be flown into Ie Shima on two disarmed G4M “Betty” bombers serving as transports. To ensure the Japanese aircraft were not intercepted and shot down, a specific air-lane between Tokyo and Okinawa was cleared, and the G4Ms were to be uniquely marked for the mission. The aircraft were to be painted white overall, with specific attention paid to eliminating the “Hinomaru” (Rising Sun, or “Meatball”) national marking. In addition, green “surrender crosses” were to be added to the G4Ms wings, fuselage, and tail. Clear instructions were given that any aircraft that appeared not marked in the prescribed manner would be destroyed. The two “Surrender Bettys” were given the codes “Bataan-1” and “Bataan-2”.

General MacArthur’s instructions from August 15th read: “Such airplanes will be painted all white and will bear upon the side of its fuselage and the top and bottom of each wing green crosses easily recognizable at 500 yards.”

As the Japanese transports approached Ie Shima, they were picked up and escorted in by a pair of B-25J medium bombers from the 345th Bombardment Group. Nearby, a B-17 “Dumbo” air-sea rescue plane stood by in case of emergency. At high altitude, a squadron of P-38 Lightning fighters (80th Fighter Squadron) provided top cover for the operation.

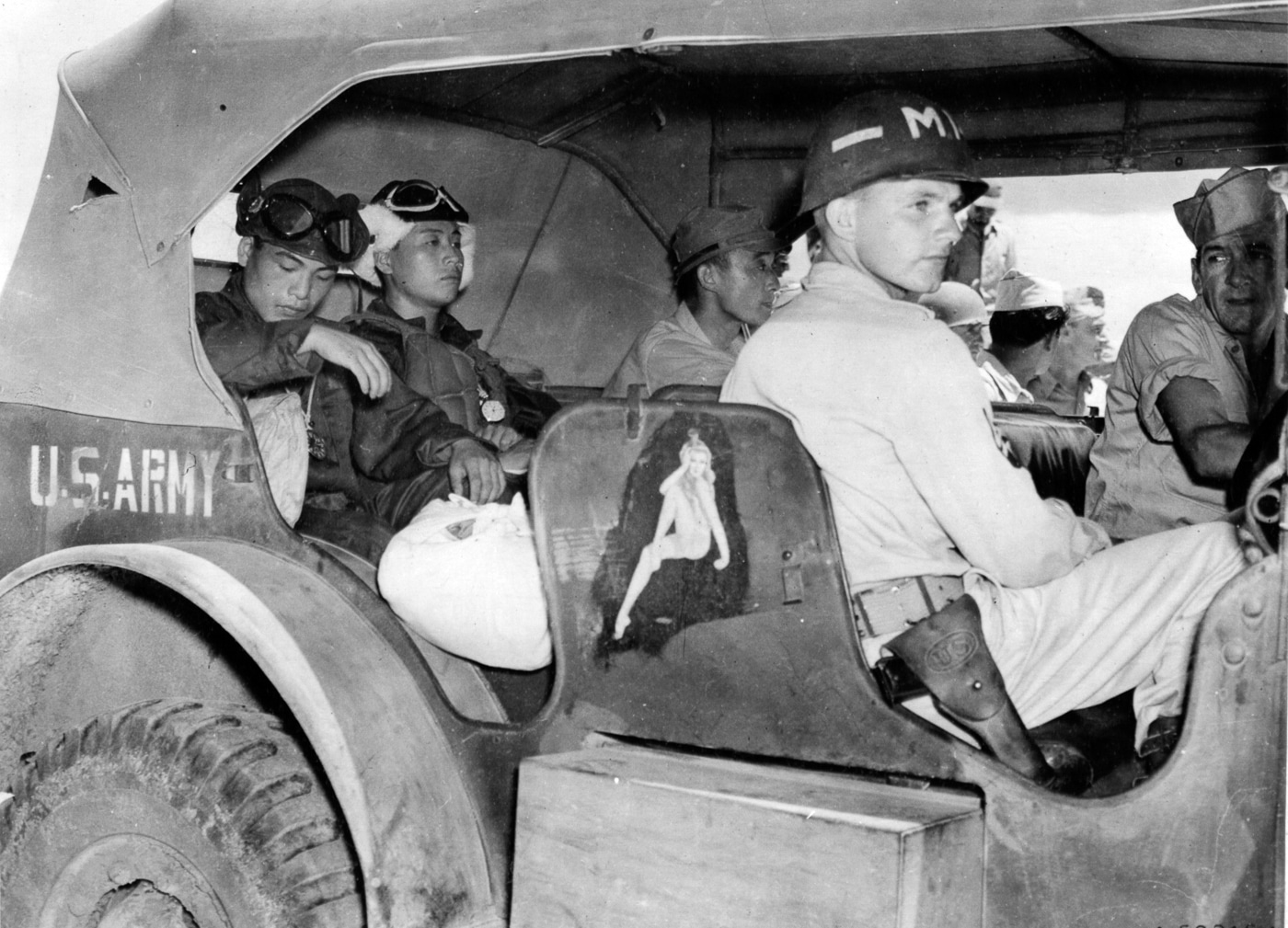

On August 19th, the surrender Betty’s reached Ie Shima without incident. As the 16-man Japanese delegation disembarked from their transports, they were met by a group of giant U.S. servicemen. General MacArthur had ordered that only men standing 6’6” or taller would interact directly with the Japanese officials — the tall man team had been flown in specifically for the event. The “Surrender Betty” crewmen carried the delegates luggage across the airfield to a waiting Douglas C-54 Skymaster transport — an aircraft with up to a 4,000-mile range.

The Japanese officers in the delegation, led by Lieutenant General Torasirou Kawabe, Vice Chief of the Japanese General Staff, carried no sidearms, but were allowed to retain their ceremonial katana swords for the flight. After a short wait, most of which was spent in the shade of the giant C-54’s wing, the Japanese awkwardly boarded the C-54 — the ground crews had removed the normal airliner-style boarding ramp and replaced it with a simple stepladder. General Kawabe was given instructions as to what to expect on their flight and that the delegation would receive further instructions when they reached Manila for the formal surrender of Japan.

While the Japanese delegation was in Manila, the Surrender Betty crews were held as prisoners of war. They were well treated, but were POWs, nonetheless. Interestingly, while one of the G4Ms was being towed into a revetment, it suffered an accident that resulted in minor damage to one of the landing gear struts. The Japanese crew and American flight engineers worked together to repair it. This may have been a tiny incident, but the cooperation signaled that real peace could be won.

When the Japanese delegation returned from Manila aboard the C-54 transport, the white G4Ms were refueled and took off to carry the delegates and the surrender documents back to Tokyo. A mistake in calculating gallons to liters caused one of the Bettys to run out of fuel and ditched in the sea near the coast of Japan. Everyone aboard was saved, and fortunately the critical documents were on the G4M that landed safely in Tokyo.

The surviving Surrender Betty was kept at Kisarazu aerodrome, about an hour away from Tokyo. A group of liberated American POWs were photographed atop the aircraft in early September. The all-white G4M was scrapped by the end of the year by U.S. occupation forces.

Meeting in Manila

After landing in Manila, the Japanese delegation was taken to City Hall, still surrounded by the signs of the fierce struggle for the city that had taken place during February 1945. General MacArthur had been given ultimate authority to accept the Japanese surrender in his role as the Supreme Allied Commander. The Japanese delegates had full authority to enact their nation’s unconditional surrender. For their part, the Japanese mostly expected brutal treatment. They knew the strict terms of the Potsdam Declaration, as well as President Truman’s warning: “Surrender or expect a rain of ruin from the air the like of which has never been seen on this Earth.” The two atomic bomb attacks had provided a devastating preview of that threat.

General MacArthur had a commonsense plan for dealing with the Japanese. He knew he held all the cards and so proceeded with a “firm but fair” style that eased Japanese fears about the destruction of their nation. The war must end, and their surrender would preserve the life and culture of Japan. The meetings in Manila were short, but to the point and fully actionable. The Allied occupation of Japan would commence shortly. Notions of Japanese resistance was neutralized by MacArthur’s fairness, and the Japanese delegation’s respect for him. The “interim surrender” was concluded without objection. The large, public ceremony for the formal surrender awaited, with representatives from all Allied nations gathering aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945.

Witness to History

My old pal Marty Richards offered some unique insight into the arrival of the G4M Betty bomber-transports at Ie Shima. Sgt. Richards was part of the 388th Air Service Squadron, supporting the U.S.A.A.F. aircraft based on the island. He was on the flightline as the Japanese peace delegation arrived.

Marty described his experiences on Ie Shima in his wartime memoir “By Air, Land, and Sea” (Armor Plate Press 2012):

“After another day of sailing, we landed on a small island called Ie Shima on August 6, 1945. It was a tiny island but there had been a lot of Japanese soldiers dug in there. This is where the famous news correspondent Ernie Pyle was killed when the Army went in to claim the island. A Japanese sniper shot Pyle and killed him instantly.

The Navy had pounded the island with big guns while carrier-based fighter-bombers dropped bombs and napalm. The Japanese were well entrenched in the caves and bunkers around the island, and it was thickly sown with mines. To take this little island the Army and Marines suffered heavy casualties.

As we were moving onto Ie Shima, the US was preparing to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These massive blasts brought about the final surrender of Japan and ushered in the Atomic Age. Negotiations for the surrender ceremonies took some time because General MacArthur wanted the event to go his way while the Japanese warlords and political hierarchy wanted to save face. MacArthur won out.

The Japanese were directed to paint two Betty bombers completely white with green “surrender crosses” on the wings, fuselage and tail. Initially the Japanese refused to do this. MacArthur told them that if they arrived in any other aircraft with any other type of markings they would be shot down. Our fighter group was to fly patrol in a certain area between Tokyo and Ie Shima. If any Japanese aircraft were spotted that were not painted white overall with green crosses they were to be shot down. Navy fighters had been given the same instructions.

The Betty bombers-turned transports landed on Ie Shima on August 19, 1945. It was obvious that they had been hurriedly painted (quickly slathered in whitewash) as directed. One of the aircraft still had bullet holes from an earlier encounter with American fighters. The Peace Emissaries disembarked from the white Bettys and were escorted to an American C-54 transport to be flown to Manila for the peace conference with General MacArthur and his staff. On the flight line, we didn’t bring out the special boarding stairs for the Japanese delegation and they had to climb up a regular ladder to get into that big C-54 transport. I took several photos that day and I didn’t realize at the time what a historic event I was capturing on film.”

Marty later told me that the maintenance crews specifically switched the C-54’s airline-style boarding ramp for a rickety old ladder, just to add a layer of difficulty and humiliation for the Japanese officials. He had been through quite a bit since he joined the U.S.A.A.F. in 1942. Along the way he had been wounded and captured by Japanese troops on New Guinea, managing to escape after 10 days without food or medical attention. He’d survived Japanese bombing raids, plane crashes, attacks by Japanese infiltrators, typhoons, and amoebic dysentery.

He confessed that he thought the ladder idea was a great joke, until he saw how old some of the Japanese delegates were. “Some of them were so old, he said, that I wondered if they could make it up the ladder without expiring. It suddenly hit me that if one of them croaked on his way up the ladder, that the peace would be off and we’d all be back to fighting the damn war again!”

Fortunately for Marty, and the rest of the world, the delegation boarded safely, and the Japanese surrender ended the war.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply