During the Cold War, aviation firm McDonnell employed some colorful monikers for its aircraft, including “Banshee” and “Demon,” which did seem like apt names for the respective carrier-based fighters. While the Banshee is now considered among the absolute best straight-wing fighters of the era, the Demon isn’t remembered so fondly, with some fleet pilots dubbing it a “lead sled.”

Yet, the infamously problem-plagued Demon may have been a better design than another McDonnell aircraft of the early Cold War-era. That would be the fittingly named McDonnell XF-85 Goblin, which was designed as a “parasite fighter” — one that could be carried by a bomber.

Just two prototypes were built before the program was canceled. Yet, the concept remains one that has earned almost mythical status among Cold War aviation buffs.

Origin of the Parasite Fighter

In theory, the XF-85 Goblin likely made sense, at least at the time it was first conceived. One first needs to understand that during the Second World War America’s long-range bombers often flew over enemy territory without any fighter escort. Even the long-range fighter escorts of the era — notably the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and North American P-51 Mustang — often lacked the range necessary to escort most bombers, not to mention those then in development. As the range of bombers increased, development began on a compact fighter that could travel with it, by being carried inside the bomber’s bomb bay.

This could allow a “parasite” fighter to provide protection for a bomber well beyond the range of conventional escorts.

Development of the XF-85 Goblin coincided with the bomber that would carry it: the Convair B-36 Peacemaker. The thinking at the time was that the massive B-36 could penetrate enemy territory while carrying the parasite along for the ride. If attacked by enemy aircraft, the bomber would lower the Goblin on a trapeze and release it to engage the attackers.

After the enemy had been driven away, the parasite could return to the B-36, hook on to the trapeze, fold its wings, and be lifted back into the bomb bay. It could even refuel and be rearmed. While the majority of B-36s in a Bomb Wing would carry the ordnance to drop on an adversary’s cities or other targets, a few would be mini-flying aircraft carriers.

The B-36 was designed to conduct missions that could see it flying a 10,000-mile round trip that could last as much as 20 hours. Thus, a small, stout aircraft like the Goblin seemed well-suited to the proposed task.

The first test flights weren’t ordered until after the World War II ended, but there were very serious (and valid) concerns that the U.S. could find itself in a war with the Soviet Union in the future and would have to deploy bombers from North America.

Enter the Goblin

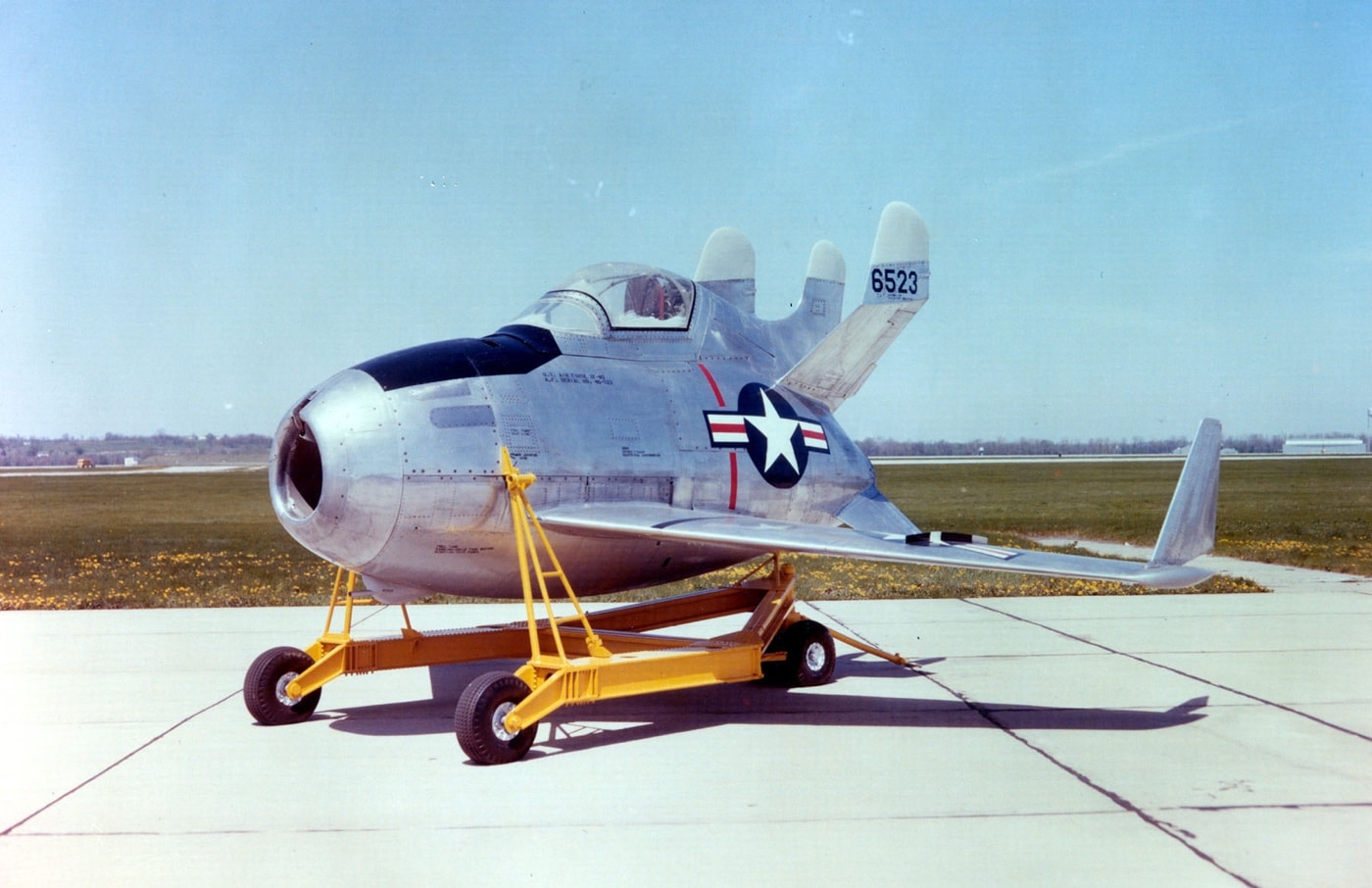

Two single-seat XF-85 prototypes were built for the testing. Each was powered by a single Westinghouse XJ-34 turbojet engine that provided 3,000 pounds of thrust, delivering a cruising speed of 225 mph and a maximum speed of 650 mph with a service ceiling of 48,186 feet.

The Goblins were unique aircraft and might have seemed to be a leap forward in aviation technology. It featured five tail surfaces, including one vertical, two angled, and two ventral. The aircraft also featured swept-back wings that could fold upward. Armed with four .50-cal. machine guns, the Goblin would have been reasonably armed for its day.

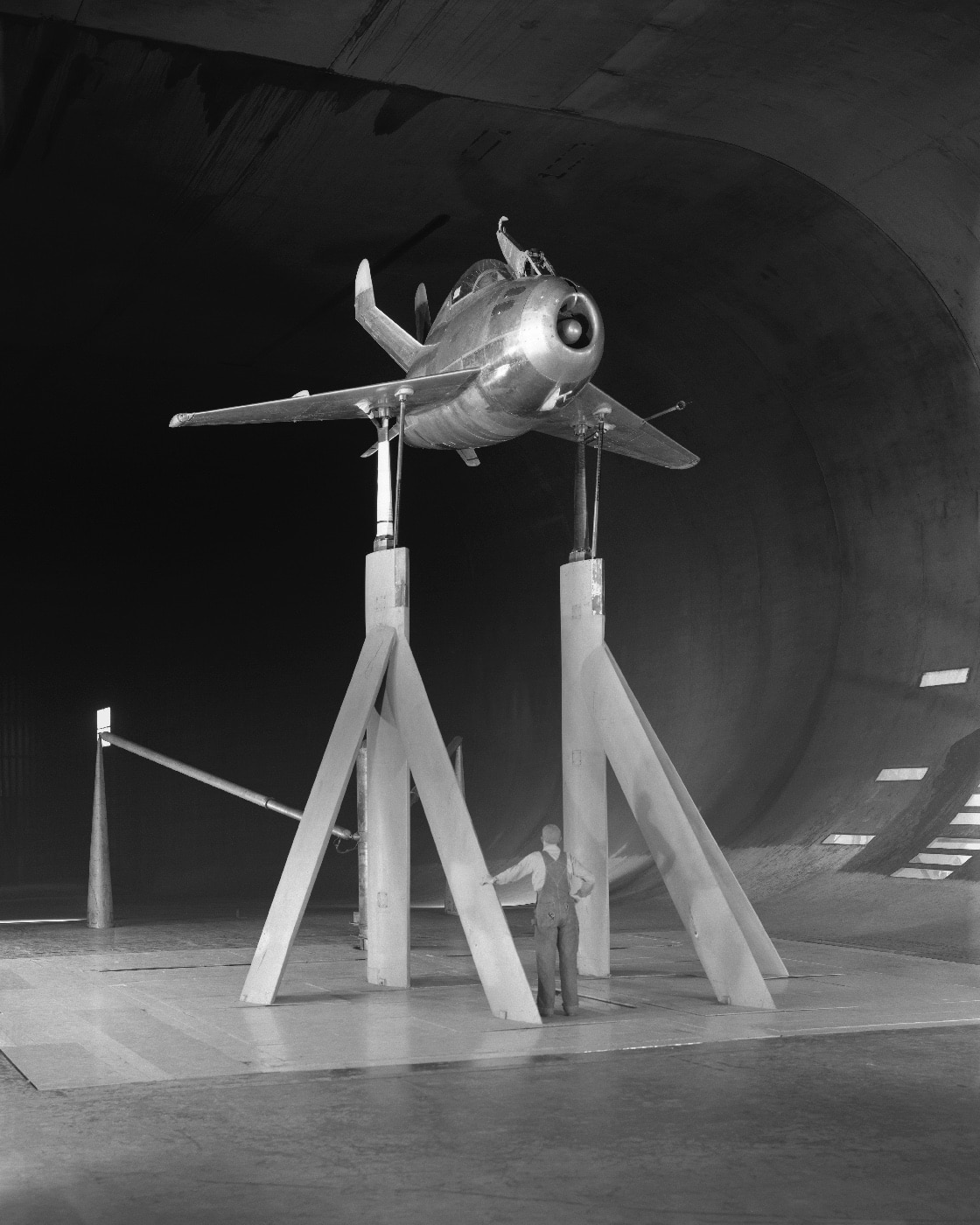

The initial tests of the Goblin were carried out with a modified Boeing B-29 Superfortress, as the B-36 was still in development. However, the Superfortress proved to be an ideal platform for the tests, which began in 1948.

Almost immediately it was determined that launching the XF-85 presented some problems, notably that turbulent air under the B-29 bomber made recovery of the Goblin difficult and at times even hazardous. The issue was that as the parasite approached the “mother plane,” the air compressed, creating stronger resistance — requiring additional power to overcome the air cushion. The higher speed actually made the air even more turbulent.

Obviously, in real-world operations that would have been a serious problem as the Goblin wouldn’t have the range to return to friendly territory if it failed to be recovered by the mother plane.

During the test flights, nearly half of the Goblin flights ended with emergency ground landings — without landing gear — when the pilot couldn’t hook up with the trapeze. In one final attempt, the fighter’s hook missed the trapeze, but the canopy struck it and shattered.

It should be noted that just a single test pilot, U.S. Navy aviator Ed Schoch, who had flown the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver during World War II, ever flew the XF-85. Fortunately, while he made several rough landings, Schoch walked away from each one.

Testing was ended in late 1949 after just seven flights, totaling two hours and 19 minutes. Aerial refueling of conventional fighter aircraft was seen as offering greater promise, and the Goblin was grounded. No XF-85s were ever launched or even carried by a B-36, but the project cost was reported to total $3,210,664 — not an unreasonable amount today perhaps, but would equate to $40 million in 2024 dollars.

Could It Have Worked?

While the XF-85 Goblin didn’t progress very far, the U.S. Air Force did continue to conduct tests of parasite aircraft and how a small fighter could provide protection for a bomber on a long-range mission. None of the subsequent efforts proved any more effective, however.

Moreover, neither did some of the concepts that came before — which should have signaled that it wasn’t going to be easy going.

As early as the First World War, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had conducted tests to see if its Sopwith Camel fighters could be carried by its 23-class airships. The program ended with the conflict and was put on the back burner.

Then in the 1930s, the United States Navy briefly operated a parasite fighter — the Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk — from its airships USS Akron (ZRS-4) and USS Macon (ZRS-5). It showed limited promise, but the fighter was already bordering on being outdated and it is hard to imagine any World War II fighters could have operated from the airships. The U.S. Navy never got to find out, as both airships were lost in storms, and the sea service scuttled the program.

By contrast, the XF-85 was a major leap forward in technology. Yet, many unanswered questions remain.

As the Goblin would have had just around 30 minutes of endurance, the parasite could have only been launched when trouble approached. The fighter would have been its most vulnerable during the launch and recoveries, while its limited flight time wouldn’t have allowed it to perform other roles like scouting for enemy aircraft.

If the issue of its recovery could have been addressed, the Goblin could — in theory — have been refueled, rearmed, and be readied to do it again. As testing didn’t progress with the B-36, it remains unclear how any of this could have been accomplished.

The B-36 is a truly massive bomber, and plans called for the Peacemaker to carry three or four Goblins within its fuselage. The idea was that it would serve as a mother ship for the fighters while other B-36s delivered the bombs to the target. At one point, the U.S. Air Force even considered having 10% of the B-36 Peacemakers converted to fighter carriers, while as many as 100 Goblins would have been built to serve as fighter escorts. Yet, exactly how much fuel and extra ammunition could be carried on the modified bombers was an unanswered question. Likewise, refueling and rearming in flight was probably easier said than done, especially in the air.

The Air Force would have also needed very select pilots to fly the Goblins — men that likely weren’t much taller or bigger than the mythical creatures. According to TheAviationist.com, the Goblin’s small size would have necessitated that pilots couldn’t be taller than 5 feet 8 inches and couldn’t weigh more than 200 pounds.

The final nail in the Goblin’s coffin was the fact that Soviet fighter technology advanced at a truly rapid pace. While the XF-85 Goblin may have been able to hold its own against the early German jet fighters of the Second World War, it would have been outmatched by such warbirds as the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 and the aircraft that followed.

Further Parasite Programs

Even after the end of the Goblin program, the U.S. Air Force didn’t give up on the parasite fighter concept. The MX-1016 program (also known as Tip Tow) saw a modified B-29A carry Republic EF-84Ds on the wingtips. The program came to an end after a crash that resulted in the loss of five crewmen on the B-29 as well as the F-84 pilot.

A similar Project Tom-Tom, which also called for the parasites to be attached wingtip-to-wingtip, was canceled after it was deemed too dangerous, while inflight refueling offered greater promise.

Yet, the Fighter Conveyor (FICON) program did move past the testing stage.

FICON saw an RF-84K Thunderflash, a modified version of the RF-84F reconnaissance version of the F-84F Thunderstreak carried underneath a GRB-36 bomber — a Peacemaker converted to also serve as a recon plane. Unlike the Goblin, the Thunderflash was too large to be carried internally but hooked underneath the mother plane.

A total of 25 RF-84K FICON aircraft were produced and fitted with a retractable probe for hooking up with the modified GRB-36 bombers — of which 10 were built. However, instead of serving as escorts for bombers, the RF-84Ks were employed as reconnaissance fighters from 1955 to 1956, serving with the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (SRS). Though there were “near disasters,” the program was only canceled with the introduction of the U-2 Dragon Lady spy plane.

Fate of the Goblin Prototypes

Despite the rough landings, both XF-85 prototypes survived, and after being put in storage when testing concluded, the aircraft were sent to museums. One is in the collection of the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio. It had been previously displayed next to the museum’s Convair B-36, but since 2000, has been in the Research & Development Gallery. The museum is also home to one of three surviving RF-84K Thunderflash reconnaissance planes.

The other XF-85 Goblin is now on display at the Strategic Air and Space Museum in Ashland, Nebraska. It had been damaged following the test flights’ final emergency landing and previously was exhibited at the Norton Air Force Base before being refurbished.

Future of Parasite Aircraft

While it is unlikely that we’ll ever see future manned parasite aircraft again, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy are now developing the fittingly named “Collaborative Combat Aircraft” (CCA) program, which calls for the development of unmanned aerial systems (UAS) that could act as “loyal wingmen” for manned fighters and bombers.

Though the details regarding the CCA still have yet to come into focus, there has been speculation the drones could include parasite aircraft — able to conduct reconnaissance missions, serve in an electronic warfare (EW) capacity, or if necessary even operate as decoys for manned aircraft.

And perhaps a fitting name for those future drone parasites would be Goblin II!

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply