Military historians, professionals, and strategists attributed U.S. military victories in World Wars I and II to two basic points:

1) The U.S. possessed deeper industrial capacity to support the war, and

2) As a result of American cultural norms and values, U.S. Soldiers were better prepared to outthink their adversaries.(1)

While these variables’ impact on American success in the World Wars is debatable, the discussion frames a larger, crucial question for the U.S. Army: What should the Army focus on to remain the dominant land force in future wars?

The Army, along with other elements of the U.S. government, continually reflect on this question.(2) Most recently, the Army introduced modernization efforts, including the multidomain operations (MDO) concept and its subsequent doctrine.(3) These efforts emphasize adapting to the evolving nature of war by the integrating information and warfighting capabilities across multiple domains.

Other national capabilities, such as irregular warfare (IW) and counterterrorism (CT) forces, could be used to prevent our adversaries from escalating conflicts from competition to general war. However, if preventative IW and CT measures fail, the U.S. Army prioritizes employing smart Soldiers and synchronizing their military and intelligence actions in time, space, and purpose to generate outsized battlefield effects.

The Army may also leverage historical lessons from its past victories to think about how to address emerging battlefield challenges. Regardless of the solution, adapting to warfare’s evolving complexities and emphasizing the ability to outthink our adversaries is a critical requirement.

The purpose of this article is to advocate for increasing the American Soldier’s ability to outthink the Army’s adversaries within the MDO context, paying special attention to ensuring that Soldiers understand how to integrate technology and multidomain capabilities beyond a pure combat situation. To help illustrate this point, I briefly examine the evolution of Army doctrine from WWI to today.

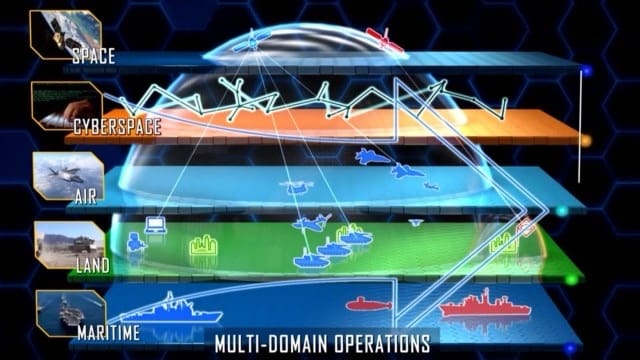

MDO Definition

In response to the 2018 National Defense Strategy Commission (NDSC) report, military scholars and professionals identified the need for a new Army operating concept to account for how the Army and the joint force would explain fighting and winning against our adversaries in new and contested domains.(4) This call to action helped fuel today’s MDO doctrine, which the Army articulates in its Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations.

FM 3-0 defines MDO as “the combined arms employment of joint and Army capabilities to create and exploit relative advantages, defeat enemy forces, and consolidate gains.”(5) MDO is the Army’s approach to address the evolving character of modern warfare by focusing on the integration of its elements of combat power across five domains — land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.(6) However, the Army went a step further and also incorporated new domains and threats, such as cyber and unmanned air systems, into MDO. Nonetheless, it is important to appreciate that many of MDO’s conceptual elements can be traced back to WWI and WWII.

Evolution of Military Doctrine

WWI and WWII

Military scholars and professionals argue that MDO principles are not new to the Army nor the Department of War.(7) During WWI, the U.S. Army synergistically combined maneuver, fire, and air support, creating a combined arms doctrine that allowed the Army to suppress enemy fire and seize objectives while applying rudimentary, multi-domain principles.(8) The Army’s use of the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” for reconnaissance and light bombing illustrates this approach. Initially produced as a training biplane, the Jenny also served in various roles, including reconnaissance and light bombing, and became one of the most iconic American aircraft of the war.(9) Similarly, in WWII, the integration of aerial artillery spotters into the Army’s existing combined arms teams also gradually nudged the Army toward multidomain operations and tactics while demonstrating how U.S. Soldiers are keenly aware of the need to outthink their adversaries.(10)

The Cold War Era AirLand Battle (ALB) Doctrine

During the Cold War, the United States and our allies needed a doctrine that could be utilized to effectively compete against the Soviets’ Red Army and the Warsaw Pact’s massive manpower pool.(11) This led to the creation of the AirLand Battle (ALB) doctrine in the late 1970s and 1980s. ALB aimed to integrate air and land forces to counter a potential Soviet invasion in central Europe, focusing on the synchronization of land and air power to create an overmatch.

ALB doctrine was built on four basic tenets:

(1) Seizing the initiative through proactive engagement with the enemy,

(2) Fighting at depth, striking targets throughout the entire operational area,

(3) Remaining agile to adapt to changing conditions, and

(4) Synchronizing operations across all domains, with all services to find the best solution to emerging militaries problems.(12)

Global War on Terrorism (GWOT): Full-Spectrum Framework (FSO)

While ALB was effective in large-scale operations, the GWOT dictated a different approach to armed conflict, leading to the development of the Army’s full-spectrum operations (FSO) doctrine.(13) FSO aimed to position the Army to thrive in the GWOT’s low-intensity conflicts and so-called small wars. During GWOT, the Army focused on counterinsurgency (COIN), IW, and CT to address the ever-present need to combat insurgents and non-state actors.(14)

This strategy enabled the Army to operate across both large-scale combat operations (LSCO) and small wars. However, the heavy emphasis on COIN, IW, and CT during this period resulted in the Army’s lack of preparedness for large-scale conflicts with near-peer adversaries.(15) Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia highlighted this issue, prompting the Army to reevaluate its operational doctrine.

Unified Land Operations (ULO)

In 2011, the Army introduced unified land operations (ULO) to describe how it would seize, retain, and exploit the initiative to gain and maintain a position of relative advantage in sustained land operations. ULO aimed to prevent or deter conflict, prevail in war, and create favorable conditions for conflict resolution. However, ULO did not account for the technological advancements made by strategic rivals like Russia and China, particularly in standoff and anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) systems.

Unconventional Warfare (UW), IW, and CT operations can fill this gap during competition short of armed conflict. Special Forces (SF) Soldiers and other UW agents can operate in the gray zone to counter the threat of standoff and A2/AD without escalating military operations into war. These small SF units and agents conduct expedient and vital military operations to extinguish small fires to prevent the proverbial forest from catching fire.(16) However, if small conflicts scale into conventional war, special operations forces (SOF) evolve their activities into direct action operations to create favorable conditions for conventional units.(17)

Recognizing the shortcomings of FSO and ULO, the Army developed and adopted MDO to account for A2/AD’s prominence in LSCO.

Multidomain Operations to Address the Emerging Threats

MDO within the Diplomacy, Information, Military, and Economics (DIME) Framework

Prior to being called multidomain operations, MDO was initially called multidomain battle (MDB).(18) However, scholars and military strategists realized the limitation of using “battle” as part of operation concept, leading to replacing battle with “operations” to include other national actions as part of MDO framework.(19) Using battle indicates actions associated with military engagements, while operations include activities outside of military domains.

From the national perspective, MDO is defined as of various national means to deal with other countries.(20) These means include diplomacy, information, military, and economics.(21) DIME outlines the four pillars used in national strategy to achieve foreign policy objectives and address security challenges.(22)

The military domains are land, maritime, air, cyberspace, and space, while the social domains include politics, economics, and information. In total, there are nine “domains” that nation-state competitions could occur: politics, diplomacy, economics, information, cyberspace, space, land operations, maritime forces, and military air forces.(23)

While politics, diplomacy, and economics fall under the executive office and Congress, and information is managed by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Department of War can influence the other five domains. During armed conflict, the military is responsible for five domains, making military actions significant factors in winning nation-state competitions. However, civilian leadership can utilize military domains at any time during nation-state competitions, but military actions are often restricted until a conflict threshold is crossed.

In the escalation of the force continuum, wars reside at the end of the continuum, while diplomacy resides on the opposite end, making military underutilized during nation-state competitions that are short of armed conflict.(24) Additionally, it is said that war is a continuation of policy with other means, making it challenging to identify when one activity ends and the other begins.

Blurred Line Between Diplomacy and War

Given that war and diplomacy exist on the same continuum, adversaries continue to blur the line between the two. Recognizing America’s military superiority, rival nations challenge the U.S. in non-military domains using methods short of war. To avoid direct military confrontation, they undermine America’s interests in other domains without crossing the threshold of armed conflict. Consequently, the blurred line between civil and military operations necessitates that military professionals stay informed about developments outside military domains. This awareness enables them to identify opportunities for contributing to nation-state competition, even in situations short of armed conflict.

Competitions Short of Armed Conflicts

Strategist Sun Tzu asserted that the greatest victory is winning a war without having to fight at all.(25) In alignment with Sun Tzu’s thinking, GEN James C. McConville posited, “In competition, our Nation’s goal remains winning without fighting by leveraging all elements of national powers.”(26) Hence, with MDO, the United States should leverage all available assets to deter our adversaries from escalating competition into armed conflict. Accordingly, even in competitions short of war, the military should play a role in deterring adversaries.(27)

For example, recognizing the blurred line between competition and conflict, the Army operationalized theater information advantage detachments (TIADs).(28) TIADs are specialized military units focused on enhancing information operations and optimizing the information environment within a specific operational theater. This capability could be leveraged by civilian authorities outside of armed conflict and employed by combatant commanders during armed conflict.(29) As a result, TIADs close the capability gap that adversaries could exploit during nation-state competition short of armed conflicts.(30) While they enhance the Army’s capabilities in information operations during competition and conflict, the evolving threats posed by an adversary’s A2/AD systems highlight the necessity for a comprehensive MDO framework to effectively counter these challenges.

The A2/AD Problem

Due to the advancement of the adversaries’ A2/AD systems, the MDO framework and capabilities are essential to overcoming these new challenges.(31)These A2/AD systems are newly developed capabilities that aim at preventing or delaying the deployment of the U.S. forces into theater or to isolate our forces from being reinforced. For example, the advancement of A2/AD allows adversaries to use long-range precision strikes and integrated air defense (IAD) systems to create standoff distance and anti-access operations while manipulating electromagnetic spectrum to isolate or disintegrate forces within their respective area of operations.(32) Ultimately, our adversaries aim to undermine U.S. military superiority using those two systems: anti-access to prevent the U.S. from reaching the theater of operations, and area-denial to disorient units when inside theater of operations.

To counter adversaries’ strategy to undermine our military superiority via A2/AD, MDO aims to penetrate and disintegrate such standoff systems to facilitate our freedom of movement in and outside the theater of operation and freedom of maneuver within the battlespace.(33) The creation of multidomain units, such as the Army’s multidomain task force is an modernization effort designed to overcome A2/AD problems by posturing forces inside theater of operations to provide positional advantage.(34) The positioning of these MDO capabilities intends to overcome the A2/AD challenge by increasing multi-national and multi-services human and capabilities convergence.(35) The U.S. Army defines convergence as “the rapid and continuous integration of capabilities in all domains, the electromagnetic spectrum, and the information environment that optimizes effects to overmatch the enemy through cross-domain synergy and multiple forms of attack, all enabled by mission command and disciplined initiative.”(36)

To implement convergence, MDO prioritizes the synchronization of multiple assets to produce a great battlefield impact, also called synergy. Like the integration of land forces with aircraft in previous conflicts, synergy is the simultaneous employment of multiple military assets to produce greater effects on the battlefield and create multiple dilemmas for the enemy. Ultimately, MDO aims to overwhelm adversaries by simultaneously executing multiple actions across multiple domains to create a dilemma for the enemy to create a window of vulnerability to exploit.(37)

Recommendations

Integrating MDO Strategies Beyond the Battlefield

MDO emphasizes synchronization of multiple military efforts to achieve a greater military outcome. This approach should be extrapolated to other national efforts beyond just military actions. For example, during nation-state competitions, the United States should synergistically and continuously employ all nine domains to create continuous dilemmas even during competition short of armed conflicts. An example of this recommendation is demonstrated by what COL Mike Rose, 3rd Multi-Domain Task Force commander, asserted: “The U.S. Army needs to constantly advance and transform to not only combat foes but help ally nations with humanitarian assistance as well.”(38) This mindset demonstrates looking beyond the traditional role of the Army by examining other national and global initiatives.

Integrating Intellectual Growth into MDO Modernization

Future MDO modernization efforts should encompass not just the integration of military capabilities across multiple domains, but also a robust emphasis on Soldiers’ cognitive capabilities to outthink adversaries. The Army should prioritize intellect alongside technological advancement, ensuring that Soldiers are equipped to navigate the complexities of modern warfare. In alignment with this recommendation, GEN Charles Flynn explained, “Weapons are important, but weapons and material are not going to win, organizational change is what is going to drive our solutions.”(39) Organizational initiatives such as recruitment programs, Soldiers’ quality of life projects, and continuous education program are an essential part of getting the right Soldiers into the Army formation and developing them to perform effectively in complex operational environments.

Integrating AI to Future MDO Modernization Efforts

Future MDO efforts should put more emphasis on artificial intelligence (AI) integration to enhance greater situation awareness and responsive decision-making processes. To demonstrate the vital need of this capability, COL Rose explained, “The Tactical Intelligence Targeting Access Node allows us to integrate terrestrial, airborne, stratospheric and space center data to accelerate our abilities to understand the environment.”(40) As the battlefield becomes more complex, technology that could aid in quick and accurate decisions will be invaluable for military leaders. Hence, incorporating AI modernization initiatives now could increase operational advantages in future fights

Conclusion

While material and technological modernization efforts are being prioritized, Soldiers’ ability to outthink adversaries is the determining factor in winning past wars. Therefore, the prioritization of intellect should drive how the Army implements Soldier recruitment, conducts operational training, performs leadership development, and arranges organizational structure.

Like the two factors that determine the outcomes of WWI and WWII, winning future wars will depend on Soldiers’ ability to outthink adversaries and the availability of the U.S. military-industrial complex to support the war. We must enhance the MDO framework by expanding its application beyond military actions to include all nine domains — politics, diplomacy, economics, information, cyberspace, space, land operations, maritime operations, and air operations.

Moreover, this article emphasizes the importance of developing Soldiers’ cognitive capabilities alongside technological advancements, advocating for robust training programs. Finally, the article recommends integrating AI to improve situational awareness and decision-making. These strategies aim to prepare the military to outthink adversaries and maintain superiority in future conflicts.

Notes

1 Martin Van Creveld, The Transformation of War: The Most Radical Reinterpretation of Armed Conflict since Clausewitz (New York: Free Press, 1991); Wiliamson Murray and Allan R. Millett, A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000); Martin Blumenson, “Review: The American Way of War,” Armed Forces & Society 2/4 (Summer 1976): 595-599, www.jstor.org/stable/45345986.

2 U.S. Army, “Army of 2030,” Army News Service, 5 October 2022, www.army.mil/article/260799/army_of_2030; “The Future of the Battlefield,” Global Trends, April 2021, www.dni.gov/index.php/gt2040-home/gt2040-deeper-looks/future-of-the-battlefield.

3 U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command Publication 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, 6 December 2018, adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-3-1.pdf; Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, March 2025, armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN43326-FM_3-0-000-WEB-1.pdf.

4 “Evaluating DoD Strategy: Key Findings of the National Defense Strategy Commission,” Congressional Research Service, 19 March 2019, crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11139/2.

5 FM 3-0.

6 Tom McCuin, “Brigades Lead Transforming in Contact Initiative,” Association of the U.S. Army (AUSA), 22 October 2024, www.ausa.org/news/brigades-lead-transforming-contact-initiative.

7 Geir eidell Nedrevage, “What is a Domain? Understanding the Domain Term in Mult Domain Operations,” Forsvaret, 2023, fhs.brage.unit.no/fhs-xmlui/handle/11250/3087369.

8 MAJ Jose L. Liy, “Multi-Domain Battle: A Necessary Adaptation of U.S. Military Doctrine,” (School of Advanced Military Studies, 2018), apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1071121.pdf.

9 Ibid.

10 MAJ Edward Richardson, CPT Bol Jock, SSG Maggie Vega, and Mark Colley, “Testing the Newest Army Long-Range Weapons System: Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon and Mid-Range Capability,” Field Artillery Professional Bulletin 24/2 (2024), www.dvidshub.net/publication/issues/71667/#page=54; William G. Dennis, “U.S. and German Field Artillery in World War II: A Comparison,” The Army Historical Foundation, armyhistory.org/u-s-and-german-field-artillery-in-world-war-ii-a-comparison.

11 FM 100-5, Operations, August 1982, archive.org/details/FM100-5Operations1982.

12 Ibid.

13 COL Grant S. Fawcett, “History of U.S. Army Operating Concepts and Implications for Multi-Domain Operations,” (School of Advanced Military Studies, 2019), apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1083313.pdf.

14 Jared M.Tracy, “From ‘Irregular Warfare’ to Irregular Warfare: History of a Term,” Veritas 19/1 (2023), arsof-history.org/articles/v19n1_history_of_irregular_warfare_page_1.

15 COL Gregory Wilson, “Anatomy of a Successful COIN Operation: OEF-Philippines and the Indirect Approach,” Military Review (November-December 2006), www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/PDF-UA-docs/Wilson-2008-UA.

16 “U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF): Background and Considerations for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 4 March 2025, crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS21048.

17 Ibid.

18 COL Marco J. Lyons and COL (Retired) David E. Johnson, “People Who Know, Know MDO: Understanding Army Multi-Domain Operations as a Way to Make It Better,” AUSA, November 2022, www.ausa.org/sites/default/files/publications/LWP-151-People-Who-Know-Know-MDO-Understanding-Army-Multi-Domain-Operations-as-a-Way-to-Make-It-Better-28NOV22.

19 Ibid.

20 David S. Alberts, “Multi-Domain Operations (MDO): What’s New, What’s Not? Presentation to 23rd ICCRTS,” November 2018, static1.squarespace.com/static/53bad224e4b013a11d687e40/t/5bf59e2bb8a0458f9489209a/1542823467565/23rd_ICCRTS_presentations_51.

21 Nedrevage, “What is a Domain?”

22 Dr. Harry R. Yarger, Strategic Theory for the 21st Century: The Little Book on Big Strategy (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College Press, 2006), press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/723.

23 Nedrevage, “What is a Domain?”

24 Ibid.

25 Sun Tzu, The Art of War, classics.mit.edu/Tzu/artwar.

26 “Army Multi-Domain Transformation: Ready to Win in Competition and Conflict,” Chief of Staff Paper #1, 16 March 2021, api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2021/03/23/eeac3d01/20210319-csa-paper-1-signed-print-version.

27 Alberts, “Multi-Domain Operations;” Nedrevage, “What is a Domain?”

28 Mark Pomerleau, “Army Tests New Information Unit in Pacific,” Defense Scoop, 23 August 2023, defensescoop.com/2023/08/23/army-tests-new-information-unit-in-pacific.

29 Ibid.

30 Fawcett, “History of U.S. Army Operating Concepts.”

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid; Lyons and Johnson, “People Who Know, Know MDO.”

33 Ibid.

34 Tristan Lorea, “‘Transformation in Contact’ Changes Army Approach to Combat,” AUSA, 16 October 2024, www.ausa.org/news/transformation-contact-changes-army-approach-combat.

35 Ryan R. Duffy, “Convergence at Corps Level: Bringing It All Together to Win,” (Army Command and General Staff College, April 2020), apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1158906.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 SGT Daniel Lopez, “Multi-Domain Transformation in a Complex World,” 16 October 2024, www.dvidshub.net/news/483285/multi-domain-transformation-complex-world.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

By CPT Bol Jock

CPT Bol Jock, PhD, is a Field Artillery officer with the Fire Support Test Directorate (FSTD) at Fort Sill, OK. In his current role, he is the battery commander for FSTD and the operational test officer for the Army’s newly developed long-range missile systems, the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon System (LRHW) and Mid-Range Capability (MRC). CPT Jock’s previous position included foreign military advisor to the Royal Saudi Land Forces, brigade fire control officer, battery commander, company fire support officer, and platoon fire direction officer. CPT Jock has a Ph.D. in industrial and organizational psychology. His dissertation examined the correlations between authentic leadership and the workplace motivations of millennial information technology engineers.

This article appears in the Winter 2025-2026 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine or www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry.

You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply