Work is currently underway on the third Gerald R. Ford-class nuclear-powered supercarrier at Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding in Newport News, Virginia. The warship is also the first aircraft carrier to be wholly designed and built through digital platforms. When launched, the future CVN-80 will also be the ninth United States naval ship and third aircraft carrier to bear the name USS Enterprise.

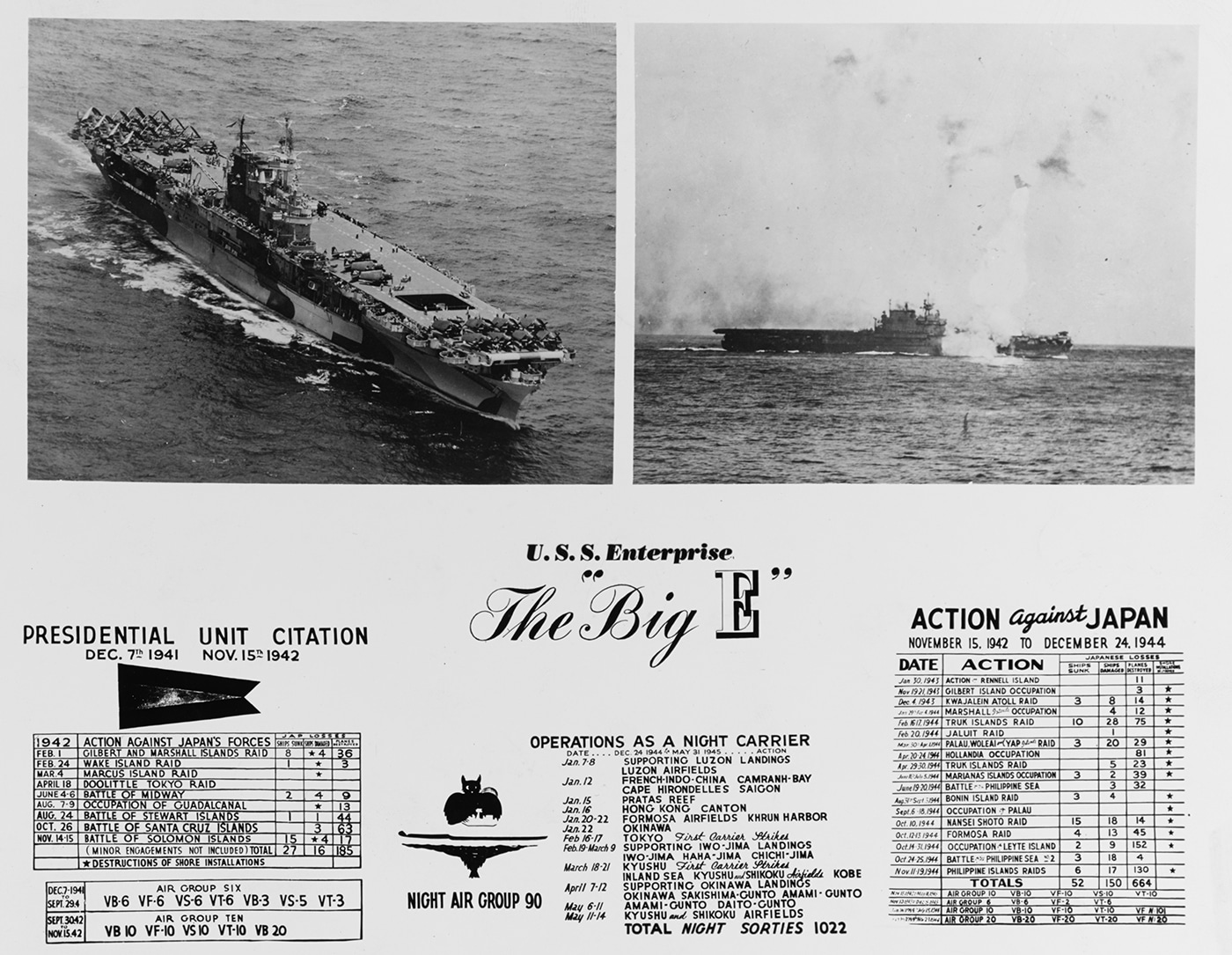

Although there have been 10 warships named USS Ranger, “Enterprise” ranks as the second most commonly used name, shared by the monikers USS Washington and USS Wasp. More importantly, the name USS Enterprise has a historic legacy, with CVN-65 being the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, while CV-6, which earned the nicknames “The Big E” and the “Lucky E” is noted for earning 20 battlestars, the most of any warship in the Second World War, as well as a Presidential Unit Citation, and even a British Admiralty Pennant.

CV-6 further has the distinction of having participated in more major actions against the Japanese military than any other United States Navy warship during World War II. Those contributions resulted in CV-6 becoming the most decorated U.S. vessel of the conflict. The USS Enterprise was also the only Yorktown-class ship and one of three United States Navy fleet carriers commissioned before the start of the war to survive the conflict.

The famed carrier was finally retired in the late 1950s, but efforts to preserve the vessel as a floating museum fell through, and in 1958, the majestic warship was sadly scrapped.

The Origins of CV-6 and the Yorktown-class

Although USS Enterprise (CV-6) (which, going forward will be the only “Enterprise” discussed unless otherwise noted by the hull number) earned numerous distinctions, including the highest decorations of any U.S. Navy warship during World War II, she was not actually the first U.S. Navy carrier to be built from the keel up. That honor goes to the USS Ranger (CV-4), while prior U.S. carriers were conversions from other ship types.

CV-4 was relatively small, just 730 feet in length, while displacing less than 15,000 tons. Beyond her small size, that carrier proved to be too slow to be effective as a first-line unit, a fact already seen by naval leaders as the clouds of war gathered. As a result, when the war broke out, USS Ranger was deployed to the Atlantic Ocean, where Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine was considered the weaker opponent than the Japanese Imperial Navy (IJN). However, it was no pleasure cruise, and the carrier took part in combat operations, providing air support for the Operation Torch landings in North Africa, and later in Operation Leader, the air attacks on German shipping off the Norwegian coast.

More importantly, the USS Ranger influenced the design of the Yorktown-class carriers, drawing lessons from CV-4’s operational experience in the mid-1930s. That resulted in larger and more capable flattops. The United States Navy went on to build three of the new Yorktown-class warships, which have been described as the first “successful” purpose-built American carriers, even as they were constructed to comply with the stringent terms of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922.

That treaty stipulated that the U.S. Navy’s carrier fleet was to be limited to 135,000 tons (137,160 tonnes) of new construction, and individual ships were not to exceed 27,000 tons (27,432 tonnes) in displacement. Initially, that allowed for the construction of just two Yorktown-class carriers, along with the smaller USS Wasp (CV-7). However, after Japan withdrew from the treaty, the United States Navy built the third Yorktown-class flattop, USS Hornet (CV-8).

All three were built at Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co., Newport News, the same facility now building the aforementioned CVN-80.

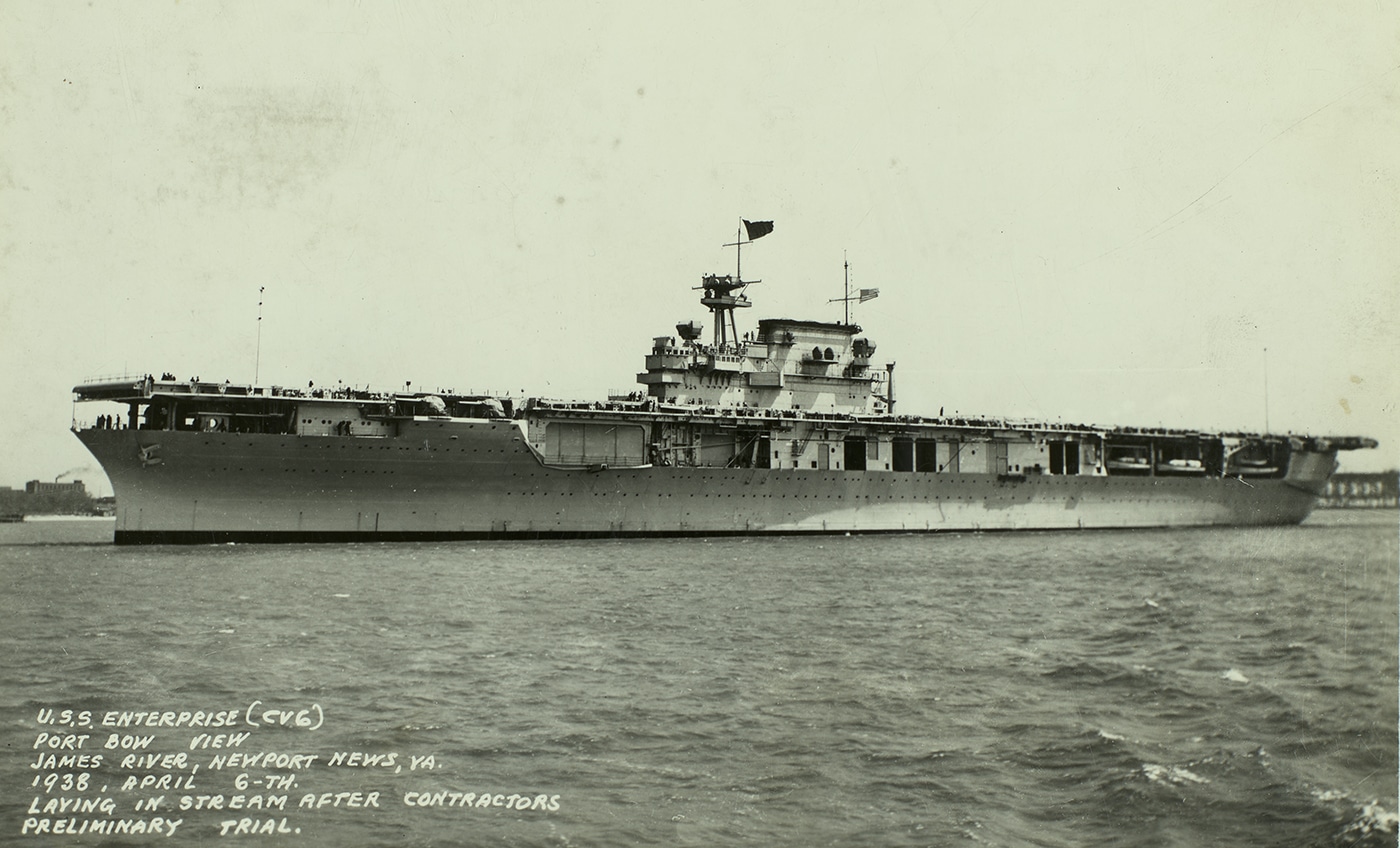

CVN-6 was laid down on July 16, 1934, launched just over two years later on October 3, 1936, and commissioned on May 12, 1936. USS Enterprise was the sixth aircraft carrier built for the U.S. Navy. At that point, the IJN already had five flattops in operation, two of which were scheduled for completion by 1939, and three more were under construction. The U.S. was beginning to lose a critical naval arms race. By 1941, the IJN would be a more potent naval force than the combined Allied fleets in the Pacific — a situation that should concern modern naval analysts, as China is now rapidly building modern aircraft carriers as Beijing expands its navy.

Yet, in the early stages of the Pacific War, the USS Enterprise played a vital role not only in leveling the playing field but in utterly upending it. By the end of the war, CVN-6 was still in service, and most of those IJN carriers were at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean!

By the Numbers

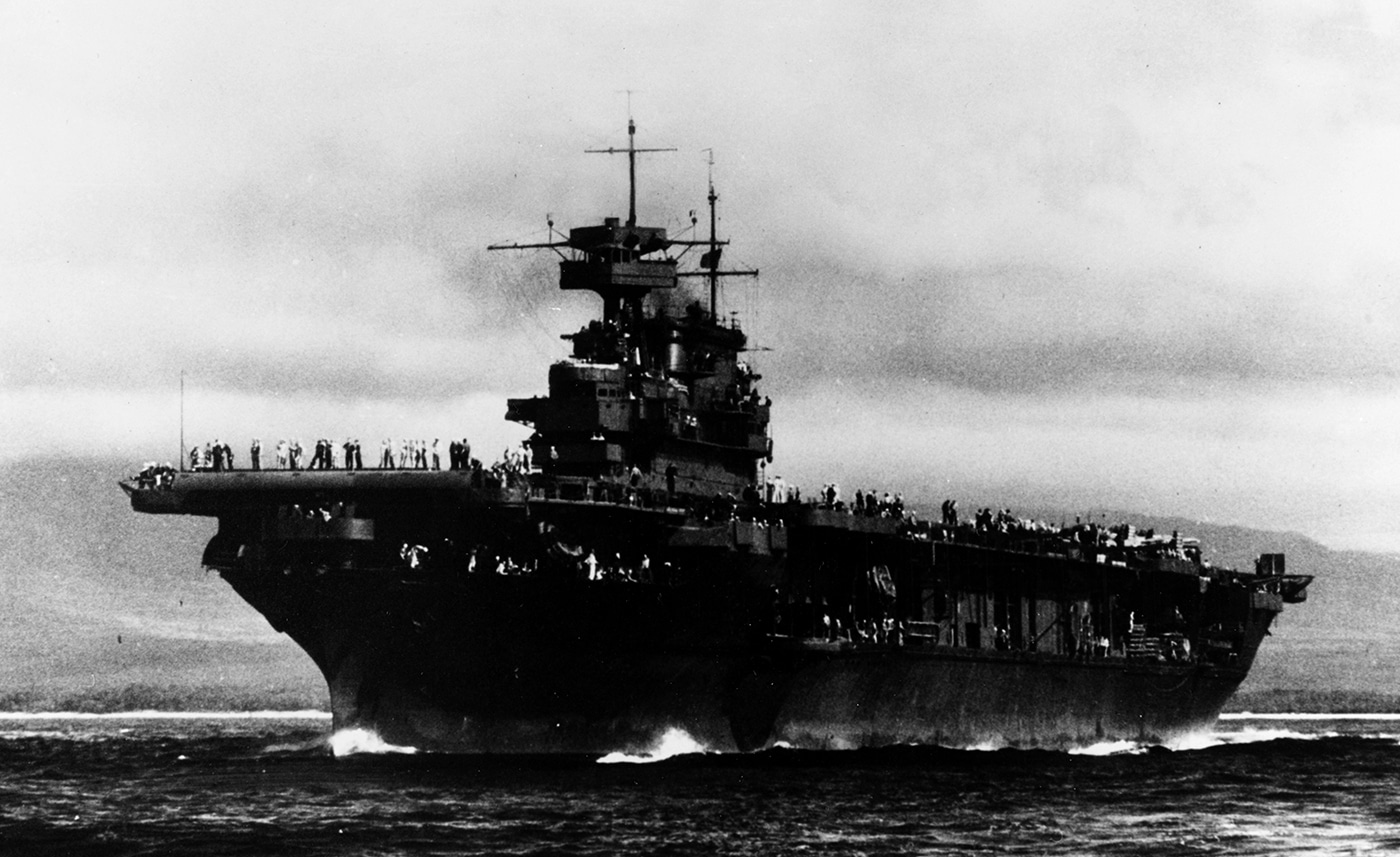

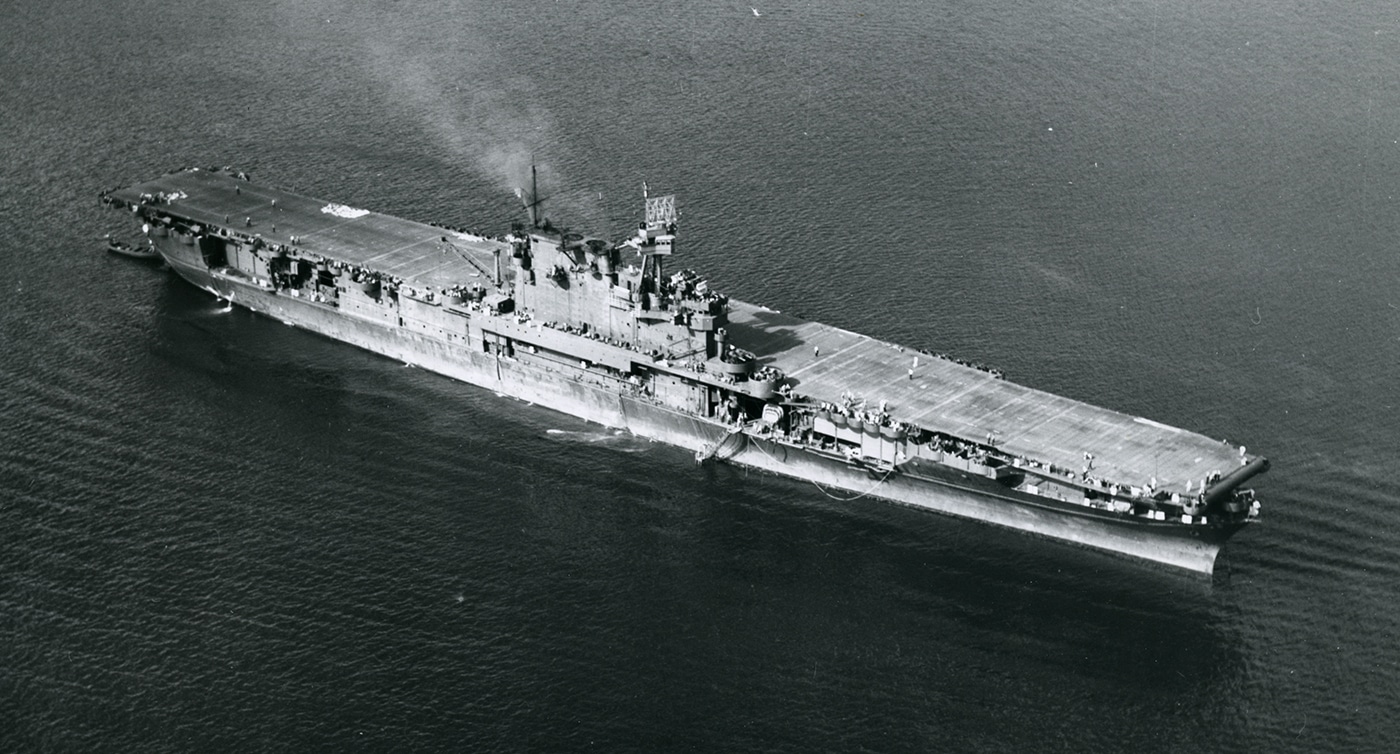

It would be fair to describe the Yorktown-class as capable but not especially extraordinary. The treaty constraints impacted their size, and as such, each displaced approximately 19,800 tons (17,962 tonnes) and, under full load, 25,000 tons (23,133 tonnes). That was increased by the end of the war to 32,060 tons full load. The warships were 770 feet long (230 meters) at the waterline and 827 feet 5 inches (252.5 meters) overall.

Powered by nine Babcock & Wilcox boilers, with a four-shaft Parsons geared steam turbine system, USS Enterprise could reach speeds of up to 34 knots, making for a speedy carrier, with a range of 12,500 nautical miles.

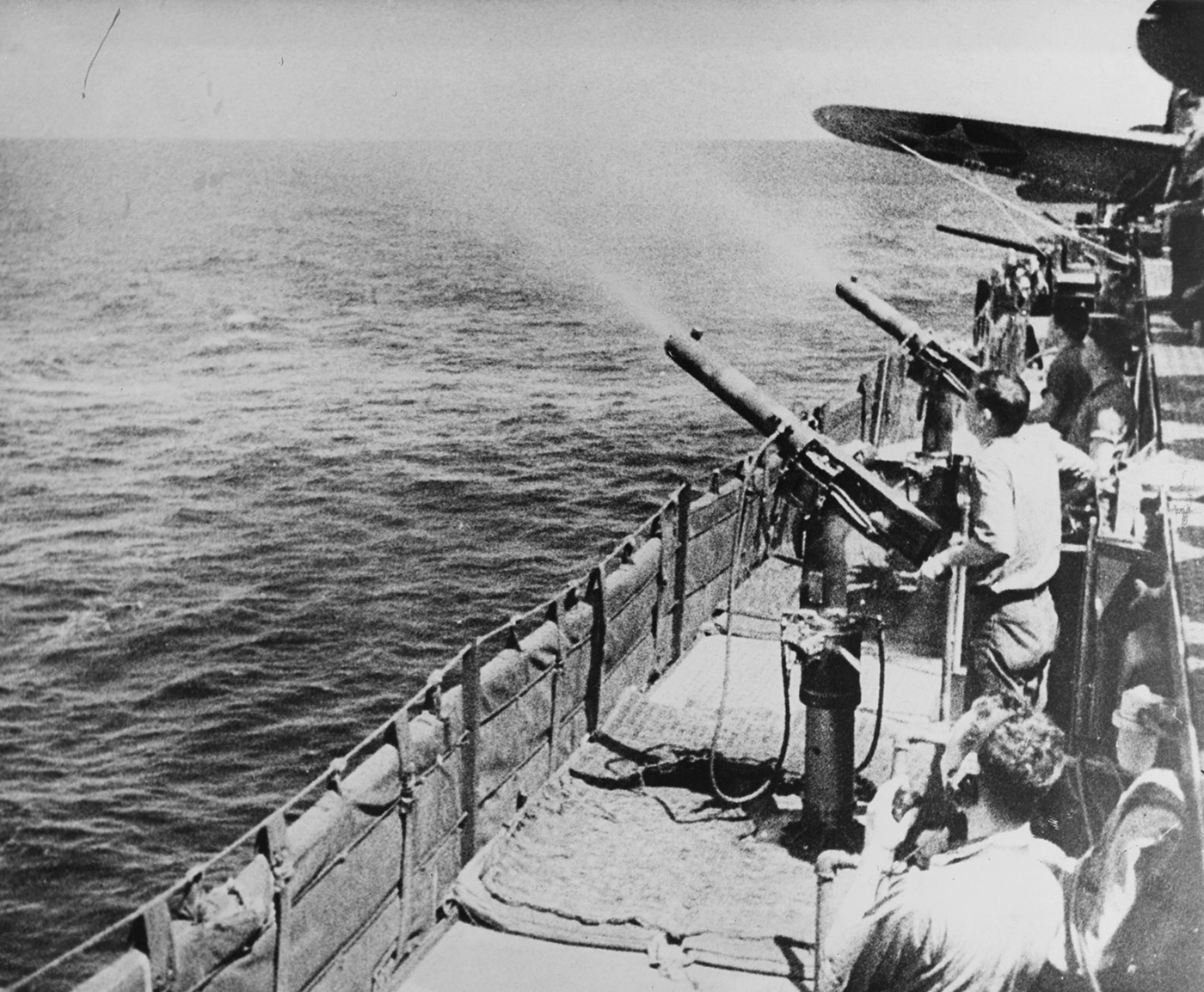

USS Enterprise‘s original air group in 1938 consisted of 18 fighters, 36 torpedo bombers, 37 dive bombers, and five utility aircraft, totaling 96 aircraft. In addition, the flattop’s initial armament consisted of 8x127mm (5-inch) guns in eight single turrets, 16x30mm (1.1-inch) machine guns in quadruple mounts, and 24×12.7mm (.50 caliber) machine guns in single mounts. By the end of the war, the 127mm armament remained, but the other defensive weapons were made up of 11 quadruple 40mm (1.5-inch) mounts, eight twin 40mm (1.5-inch) mounts and 16 twin 20mm (0.7-inch) mounts.

The carrier was outfitted with hangars that were light structures independent of the hull, and which could be closed off with rolling shutters. There were also three elevators that could be entirely enclosed by the flight deck. The early design of the Yorktown-class envisioned a flush flight deck with horizontal funnels, but this was thought to pose a smoke hazard to landing aircraft. Instead, the carriers were fitted with an island to carry funnel uptakes and provide space for control centers.

Another early design consideration was for an armored flight deck, but it was quickly determined that not enough armor could be provided to be useful without significantly increasing the ships’ weight, sacrificing speed. Instead, the flight deck carried just 76mm (three inches) of armor plate.

USS Enterprise at Pearl Harbor

When the IJN launched its sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, USS Enterprise was at sea about 200 miles (320 km) west of Hawaii. Tensions between Washington and Tokyo had been high, and the U.S. was (accurately) concerned that Japan might launch an attack on its territory somewhere in the Pacific. Intelligence suggested that an attack could likely occur on Wake Island, and it would be a surprise attack — as Japan had carried out such actions in the past, notably on February 8, 1904, when Japan launched a torpedo attack on the anchored Imperial Russian Navy’s fleet at Port Arthur in Russian-controlled China on the Liaodong Peninsula.

In November 1941, a fateful decision was made to send additional forces to Wake Island. It didn’t save the U.S. military facility, but it likely ensured CV-6 would be in the fight when she was needed most.

USS Enterprise, along with nine destroyers and three heavy cruisers — designated “Task Force 8” under the command of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey — had departed Pearl Harbor on November 28 to deliver a Marine fighter attack squadron to Wake Island and was scheduled to return on December 6, but was delayed by a storm. Some historians have suggested that it was a critical stroke of good luck for the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

The IJN was unaware of the secret mission and mistakenly expected the carrier to be among the warships at anchor in Pearl Harbor. The attack on December 7 resulted in all eight battleships being heavily damaged or sunk, with neither USS Arizona (BB-39) nor USS Oklahoma (BB-37) able to return to service.

Although CV-6 was unscathed in the raid, 18 of her SBD Dauntless dive bombers did arrive at Pearl Harbor as part of a scouting mission as the attack was underway. Seven of the aircraft were shot down, most by Japanese fighters, but at least a few were also targeted by panicked American anti-aircraft fire.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, there were valid concerns that the Hawaiian island of Oahu would be invaded. Scout planes from USS Enterprise took part in a two-day wild-goose chase seeking the IJN fleet, which rapidly withdrew to Japan. The U.S. Navy carrier had to wait for its showdown with the IJN’s carriers.

Pearl Harbor to Midway

Historians have suggested it wouldn’t be hyperbole to suggest that CV-6 was the hardest-worked aircraft of the war. She fought in nearly every Pacific campaign, and while the carrier survived the conflict, she took tremendous damage along the way.

One of the first combat actions involving the USS Enterprise after Pearl Harbor occurred on March 4, 1942. More than a month before the famed “Doolittle Raid” that saw 16 U.S. Army Air Force B-25 Mitchell bombers bomb targets in Japan, including Tokyo, the carrier took part in the raid on Japanese installations on Marcus Island, a Japanese-controlled outpost just 1,000 miles from Tokyo.

That raid damaged the base, but more importantly, it shocked the Japanese military, which had considered the island secure, while it further showcased the effectiveness of carrier-based aircraft.

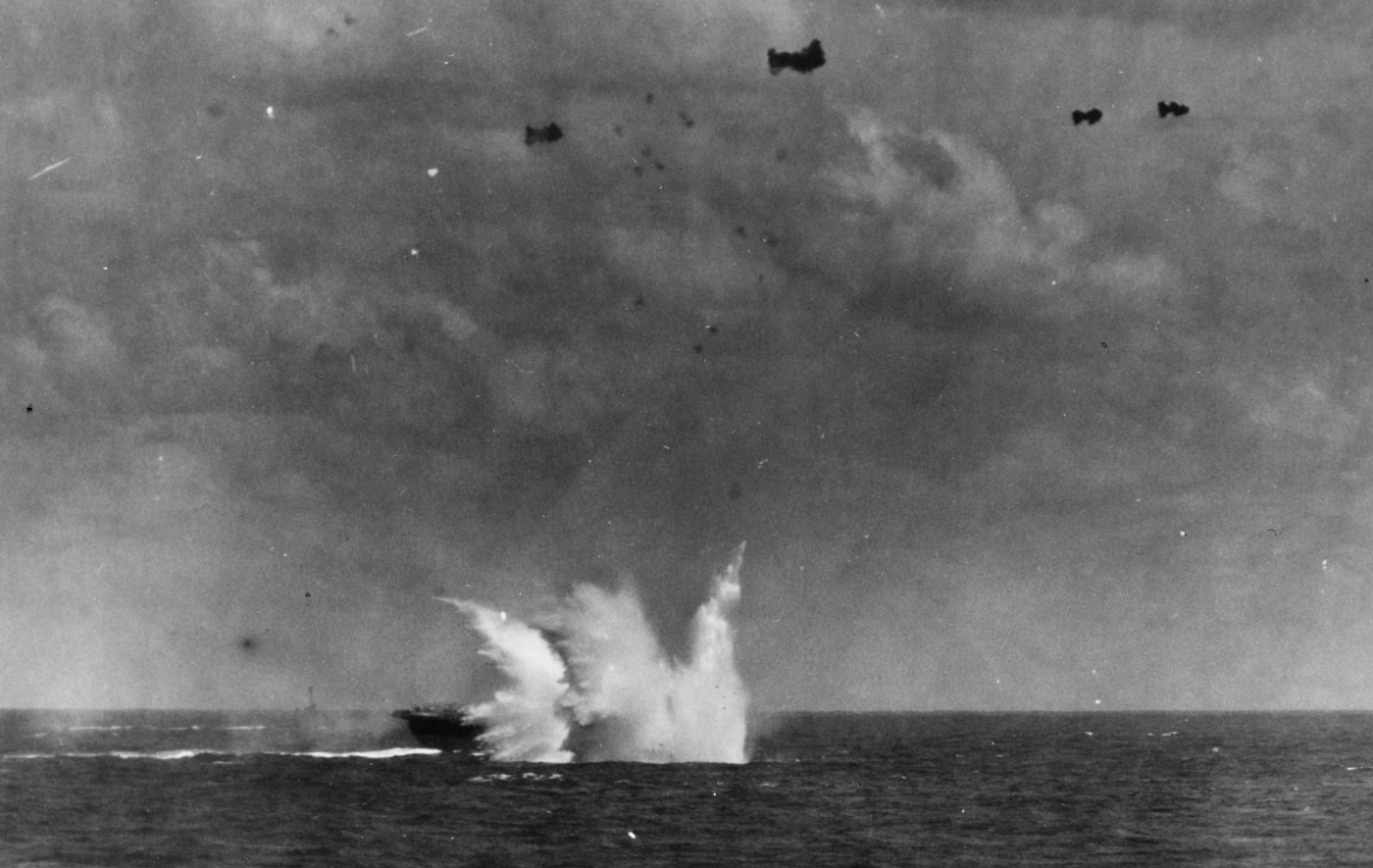

Then, six months after Pearl Harbor in June 1942, USS Enterprise helped turn the tide of the war and truly earned her place in history at the Battle of Midway. Much has been written about the battle, and it is beyond the scope of this article to go into great detail about the engagement. However, the critical part to note is that four IJN carriers that had taken part in the attack on Pearl Harbor — Akaga, Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu — were part of a flotilla that aimed to bombard the island of Midway and expand the IJN’s perimeter eastward, threatening Hawaii and even the continental United States.

The thrust towards Midway was met by a vastly outnumbered U.S. carrier force that included Rear Admiral Fletcher’s Task Force 17, with USS Yorktown (CV-5), and Rear Admiral R.A. Spruance’s Task Force 16, with USS Hornet, and of course, USS Enterprise. The U.S. Navy carriers were supported by U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Army air units based on Midway. The IJN expected another sudden surprise attack, but the force was actually heading into a carefully laid trap.

The U.S. Navy had cracked the IJN’s JN-25 naval code, and was able to determine the Japanese fleet was heading to Midway.

On June 4, 1942, aircraft from USS Enterprise and USS Hornet launched their strike groups. To summarize, those aircraft flew into destiny. The air group from CV-6 attacked Soryu with 12 TBD Devastators torpedo bombers of U.S. Navy Torpedo Squadron 3 (VT-3) and 12 SBD Dauntless dive bombers of Bombing Squadron 3 (VB-3). The U.S. aircraft successfully attacked and crippled the Japanese carrier, scoring at least three direct hits on the flight deck as it was laden with armed and fueled aircraft. That ignited massive fires that doomed the ship.

It was a costly attack, however, as only five TBDs survived to make their torpedo attack, and three of those were shot down on the way out. Many TBDs ran out of fuel and had to ditch.

The battle continued, and when the smoke cleared, aircraft from USS Enterprise had further contributed to the sinking of Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu, along with the heavy cruiser Mikuma. Hiryu was subsequently abandoned by its crew and scuttled after taking heavy damage. Once again, USS Enterprise survived the battle with no damage.

USS Enterprise: Workhorse Carrier

Despite the massive victory, which has been described as the turning point, the worst was yet to come for USS Enterprise. Two months after the Battle of Midway, CV-6 played a critical role in the Battle of Guadalcanal, providing air support for the U.S. landings and then taking part in actions in Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz. On August 24, 1942, the aircraft carrier sustained extensive damage to her flight deck, elevators, and rudder. The crew was able to make emergency repairs and she was returned to the fight. The carrier took additional damage at the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands on October 26, 1942, and then underwent emergency repairs in Noumea, New Caledonia. That marked one of the three occasions on which the IJN claimed to have sunk the USS Enterprise, which subsequently earned the aircraft carrier the nickname “The Grey Ghost.”

It was also that same month that USS Hornet was sunk, leaving USS Enterprise as the last operational American fleet carrier in the Pacific. The period was known as “Enterprise vs. Japan.”

The USS Enterprise, which also earned another nickname, “The Big E,” saw additional action in 1943 and received the Presidential Unit Citation, the first time it was awarded to an aircraft carrier. As the new Essex-class carriers began to enter service, CV-6 received a much-needed overhaul and then returned to service, seeing more action, including at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, with her aircraft later striking Paulau, Leyte, Luzon, Formosa, the Chinese coast, the black sands of Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. At the latter engagement, USS Enterprise survived two kamikaze attacks. By that point, she had become the most decorated U.S. Navy warship of the Second World War.

As the aircraft carrier had been severely damaged in a May 14, 1945, kamikaze attack, she was at Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, undergoing repairs when the Empire of Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945. However, after completing her repairs, USS Enterprise took part in Operation Magic Carpet, returning U.S. forces from the Pacific. It is unclear whether the sailors, Marines, and soldiers who were given the boat ride home were aware of the warship’s role or that she was one of just three fleet carriers in service before the war to have survived to see the final victory.

Failed Effort to Save the Big E

Despite her almost legendary combat history, the USS Enterprise was considered outdated and had inferior technology compared to the new generation of aircraft carriers. Moreover, the U.S. Navy had no shortage of carriers, which were faster, larger, and more capable.

CV-6 was decommissioned in February 1947.

Despite that fact, she was kept mothballed, redesignated CVA-6 in October 1952, and then to CVS-6 in August 1953, yet never returned to service. There were calls throughout the 1950s to preserve the only remaining carrier of the Yorktown-class as a museum, but the efforts failed to materialize. The most significant hurdle was simply a lack of money. In addition, there was the issue of the damage she had sustained, as well as the wear and tear from the war. Her upkeep would have been challenging to say the least.

Finally, there was a lack of suitable, available, and affordable locations established to take over the warship, and USS Enterprise lost the battle to see her preserved. She was scrapped in 1958, but as noted, her legacy lived on with the first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier that soon followed, while a future Ford-class supercarrier will also bear the famous moniker.

Today, various artifacts are preserved, including some of her portholes, anchors, and even a stern plate. Most importantly, the failure to save USS Enterprise for future generations also served as a wake-up call that spurred the development of the modern museum ship, and led to the preservation of other iconic warships, including four Essex-class and one Midway-class carrier.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply